Aakriti Chandervanshi, Natalie Khoo, Hong Shu-ying & Yen Duong on Inheritance

Objectifs’ sixth Women in Film & Photography showcase opened on 11 Nov 2021 with the theme Inheritance. The second of four weekly online artist talks featured exhibiting artists Aakriti Chandervanshi, Natalie Khoo, Hong Shu-ying and Yen Duong in conversation with the show’s curators, Emmeline Yong and Leong Puiyee from Objectifs.

This recap of the session has been paraphrased for brevity.

AAKRITI CHANDERVANSHI

Aakriti Chandervanshi is a visual artist, curator and designer from India whose training in architecture informs her photographic practice.

Her exhibited project After Eden documents change and resistance in twin villages Khokana and Bungamati in Nepal, whose land is under threat by slow progress on a “fast-track” expressway prioritising tourism and development. The land houses an archaeological site nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and more importantly holds both spiritual and practical significance for the native community “whose whole life cycle has revolved around the land for generations”.

Installation view of “After Eden”, Objectifs Chapel Gallery

As an architect-in-training, Aakriti was “never drawn to construction but the branch of conservation” and found working on projects about heritage advocacy most meaningful. She was also “very interested in the impact of visuals, which allow the audience to get a sense of the past, in the present”, and studied photography with Pathshala South Asian Media Institute to equip herself with these skills.

Aakriti followed the protests led by the people of the area, engaged in conversations with the communities, and examined environmental assessment reports. She elaborated: “As an outsider, I needed to know both or more sides of the story, so I talked to artists, architects, historians, activists. Archaeological as well as sentimental significance, historicity and ecological destruction are all being sacrificed for notions of ‘progress’.”

Her initial approach was to photograph from 4.30am to 7.30am, “mediating between” Bungamati where work on the fast track had already started versus Khokana where it hadn’t, “allowing us to look at what we are trying to conserve and what we would lose”. Aakriti felt that “the land was the protagonist of the work”, hence the absence of humans in her initial, very documentary-approach images.

This shifted when she had to return to India in early 2020 due to Covid-19, and started to look into the Nepal Picture Library’s archives to help address the “very many questions [she] had”. With the material generously shared with her by the archive, she questioned: “Am I trying to frame the project into something? Am I depicting what I’m seeing? Does [my take on it] really fit?”

She shared her work-in-progress with curator contacts, and “their faith in the work made me add the secondary and post-secondary material; they go side-by-side but this layer, with its images of people engaging with the land, really shows what has already been lost, and the elusive present, which is in question.”

Aakriti’s approach shifted from images without people with “the land as the protagonist” of the story, to incorporating secondary material from the Nepal Picture Library’s archives.

Aakriti continues to get updates from the community members on the ongoing battle which still has a long road ahead. She concluded: “It’s imperative to not only see them as fighting for their land but also for their history and their beliefs. The question I’d leave viewers with is how much of the people’s memories we’re willing to override for the sake of hypothetical progress. It’s testament to the community’s voice and the waves that their resistance has created.”

NATALIE KHOO

Natalie Khoo is a filmmaker, moving image artist and film programmer from Singapore with a background in archaeology and anthropology.

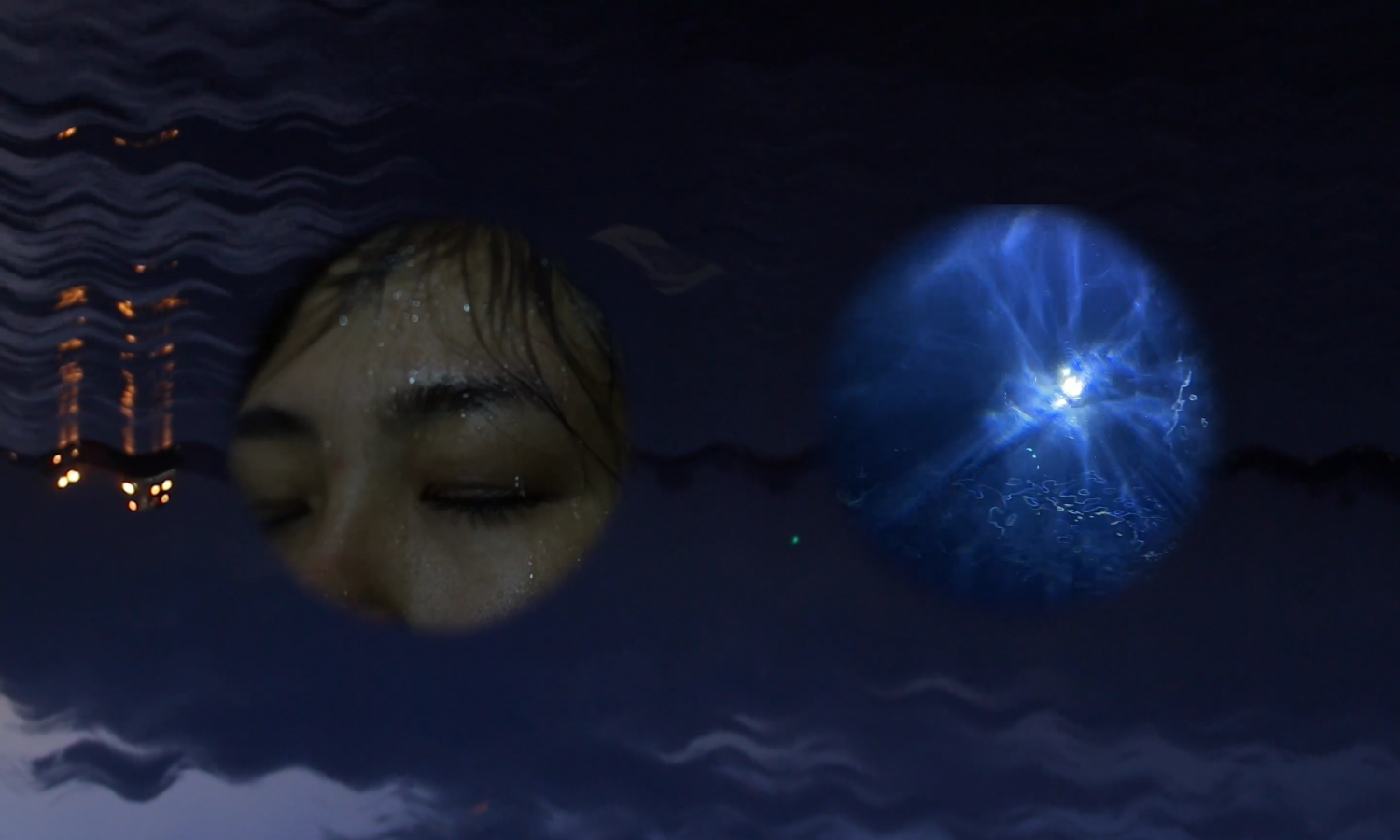

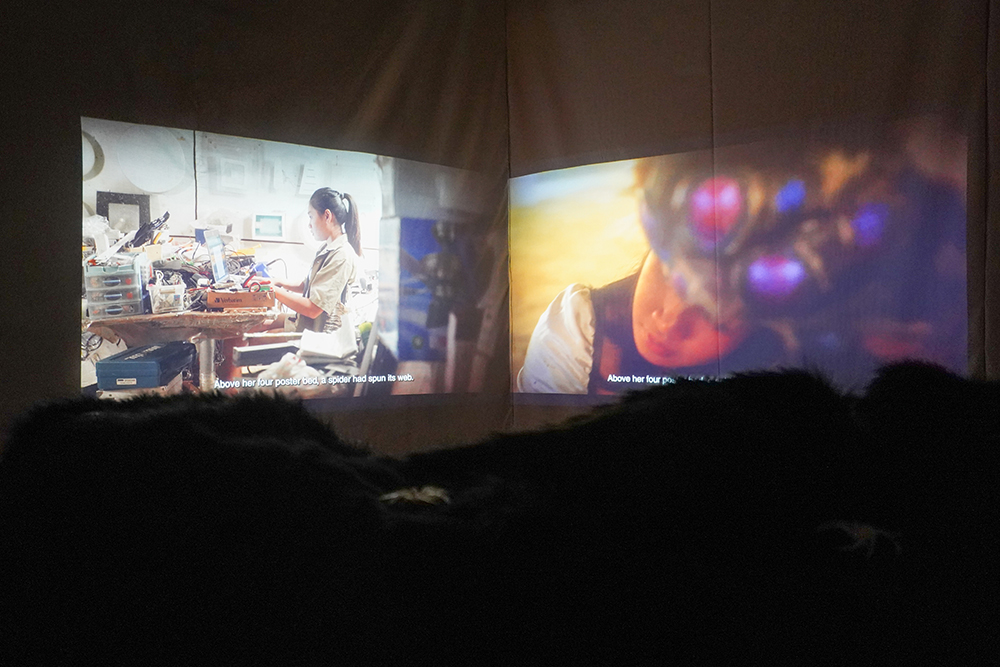

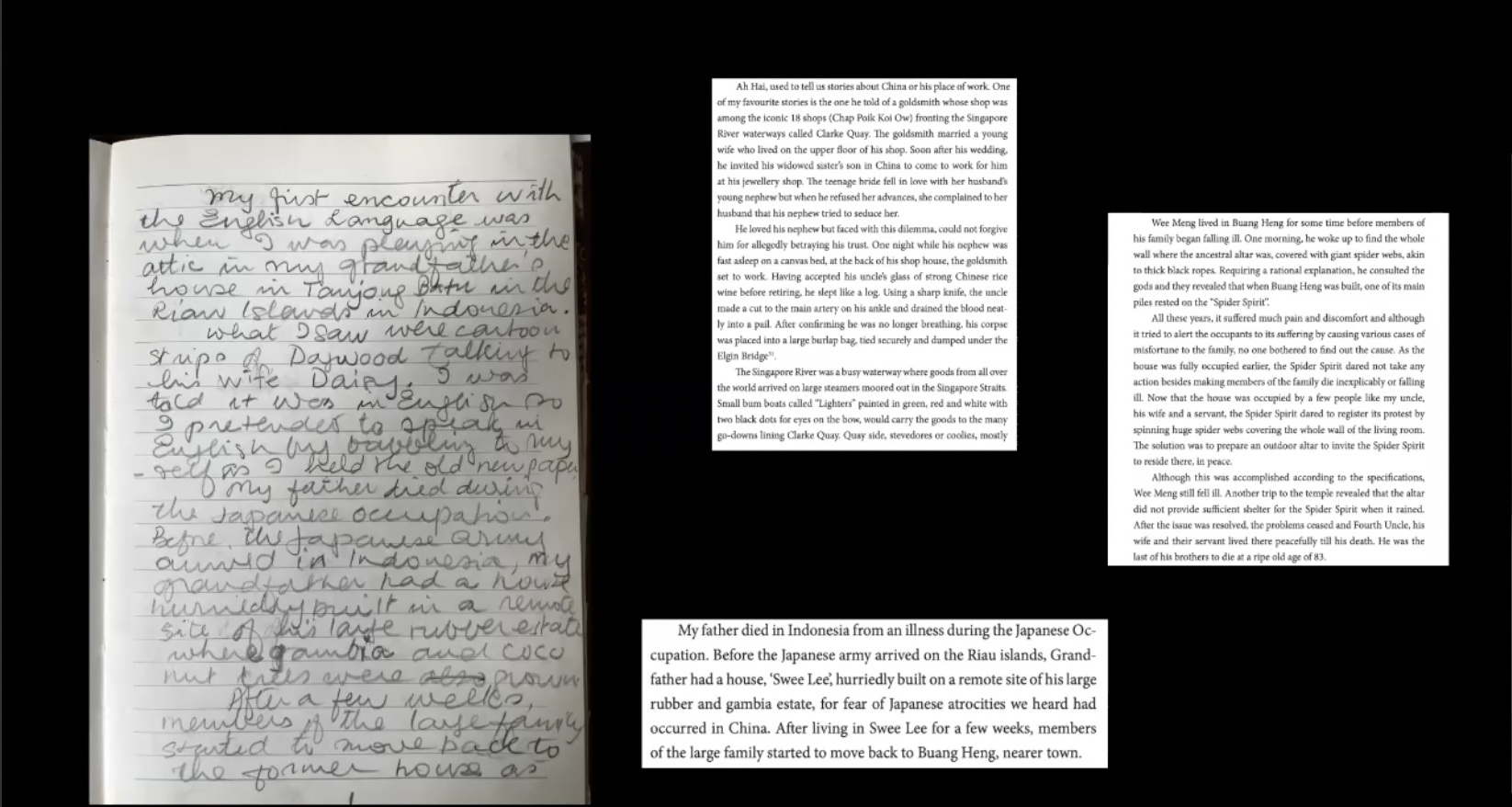

A Spider, Fever and Other Disappearing Islands, which is shown as a 2-channel installation at Objectifs, is a scriptless “act of translation” that remixes two texts: Natalie’s grandmother’s autobiography that she penned during the pandemic, and an anthropological ethnography titled Singapore, Big Village of the Dead: Cities as Figures of Desire, Domination, and Rupture among Korowai of Indonesian Papua by Rupert Stasch.

Installation view of “A Spider, Fever, and Other Disappearing Islands”, Objectifs Chapel Gallery

The docufiction-like project did not have a straightforward script or filmic process but a big group of international collaborators from animators to editors. It incorporates footage including “more classical documentary elements” such as iPhone footage of Natalie’s grandmother from 2015 and of a journey to her grandmother’s home in the Riau archipelago, and methods ranging from improvisation to 3D modelling.

Natalie elaborated on the film’s cryptic and evocative title: “There’s a stable, written version of my grandmother’s memories but every time she would tell a story specifically about a spider spirit, it became very elastic. She would forget things, add on details. And when others who had heard her story tried to retell it, it further evolved into something on their own terms.

“So this kind of collaborative process was very natural for this film, which is about the idea of storytelling, and even non-human storytellers like spirits and animals, like the spider. The story became sentient and living, continuously growing and distorting, with my collaborators working on different parts, riffing off texts and early drafts I sent them, and we remixed it all in the edit.”

Natalie’s grandmother’s autobiography revealed how the older woman, who grew up in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) and migrated to Singapore, had witnessed acts of “violence, crime, spirits, mystery, migration and intrigue”. In her grandmother’s retellings, elements from different experiences and stories mingled together, such as a murder victim whose body was stashed under the famous Elgin Bridge appearing in a dream.

Excerpts from Natalie’s grandmother’s handwritten memoirs, which Natalie was tasked to subsequently type up.

The project is also marked by “pan Asian” connections and sensibilities, not only with Natalie’s grandmother’s stories traversing geographical boundaries, but with the collaboration with editor TJ Collanto, whom Natalie met online during the Objectifs Short Film Incubator 2020. They discussed “how when we talk about Southeast Asia it is impossible to avoid discussing hegemonies and how different the countries are, as well as passages across water — we are really close by, but there’s so much intimacy and distance at the same time.”

Natalie and TJ took a “soft horror — not full-on meant to scare you” approach to exploring “our histories, which are haunting”. They were aesthetically inspired by video games like Genshin Impact, which they played to “share [their] worlds, having not yet met offline”, and “travelled” together on side quests.

In addition to geographical distance, Natalie and TJ also discussed and explored the element of time, playing with two-channel experiments about the Philippines and Singapore, reading about maps and web-building, and discussing “the idea of stories as being nonlinear and constantly growing”, and even further dimensions like syncretism, informed by Natalie’s grandmother who is Catholic but has very mixed spiritual influences.

The second text that Natalie’s film translates and reconfigures is an anthropological ethnography of the Korowai people who imagine Singapore as a “big village of the dead, something out of their reach, with glittery, neoliberal promises of jobs and the marketplace that they were excluded from.” The idea of a “psychogeography with horrific elements” resonated with Natalie, who returned to Singapore not long ago and felt it was “distant but intimate at the same time.”

HONG SHU-YING

Hong Shu-ying is a Singaporean Chinese artist who thinks in her practice about nostalgia, culture, identities and conflict. Lapping Emulations stems from a process-led investigation spanning nine months to investigate the nuances and complexities of an unstable, protean cultural identity.

Installation view of “Lapping Emulations”, Objectifs Chapel Gallery

Shu was “always oscillating between reading and making”; she read both academic papers and literature texts about migration, and spoke with older family members. She “wanted to actually internalise all this information and express it in a more emotive way, rather than just translating it”, so she chose to employ improvised darkroom and editing techniques to manipulate seaweed, which is significant to her Henghwa ancestors who originated from seaside regions of China.

As a child, Shu believed it was normal for each generation of a family to have grown up and lived in a different country, as this was her own family’s migration experience: “It was only when I grew up that I realised it was not the case that each generation’s home country would change.” Like Aakriti, she was drawn to visuals as a medium that “could more tangibly represent our many customs and values. For me and all my cousins, not all of whom could speak Chinese, food is where we continue to practise our customs”.

Shu-ying finds the Henghwa dish parmee “very interesting because it’s something everyone in the community knows, but they each have their own version of it.” But what remains constant is a seafood broth to which are added noodles, seaweed and condiments. For Shu-ying, the dedication of the “hardworking and resilient farmers” who have to endure the elements to harvest this seaweed “very specific to a geographical location” mirrors her family’s consistency in “always handing over some parts of [their] culture from generation to generation even when [they] migrate and have to readjust”.

Shu-ying conducted a process-led investigation into seaweed by manipulating it using darkroom techniques.

Upon closely examining the seaweed’s form and colours, and applying various techniques to it (such as wetting and drying it, picking it apart) in the darkroom, she also reflected on her own cultural identity: “It’s something I grew up with, and it’s always around me, but I didn’t actually notice the nuances until I spent the time and energy to do so.” She also greatly enjoyed using analogue processes as “they allow everything to be shown; I couldn’t be selective about what resulted — you got larger scales, awkward angles. Developing took time and you got to slowly observe it; the whole idea of time was not as linear and quantifiable as we are used to. It was a different way of encountering time”.

In picking apart the seaweed and presenting it in different ways, Shu also developed a “greater sensitivity to looking at forms”. “With migration, you’re always wondering how much of the host culture you want to adopt and how much of your home culture you want to maintain. You have to negotiate and manage the conflict of whether you want to develop intergenerational ties. Elements of chance and unpredictability as reflected in my processes are actually a huge part of migration. They are not usually captured in more formal and academic texts but are something I derive more from literature and speaking to my own family members. We don’t always have a choice about our particular experiences or aspects of identity; they are subjected to an element of chance.”

Shu ended her presentation by reading aloud a poem she wrote that emulates and conveys the sounds of the sea, even for audiences that cannot read or understand Mandarin. She shared: “I wanted to anchor everything down with the feeling of being at sea.”

YEN DUONG

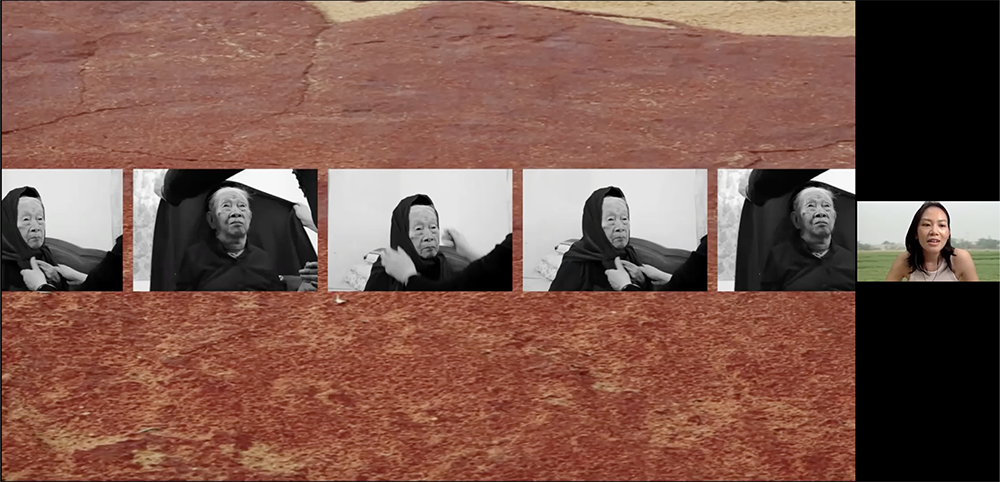

Yen Duong is a photographer based in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Alternative Imaginaries, a work-in-progress since early 2020, is “a personal visual essay exploring the intricate relationship between collective memory, private history and political amnesia in modern day Vietnam”.

Installation view of “Alternative Imaginaries”, Objectifs Chapel Gallery

Yen’s motivation to initiate this project is “rooted in [her] work as a photojournalist who works for a Western-dominated international media and is constantly confronted with different flows of information that are often really contradictory, while Vietnam is notorious for censoring news and even details of an already very contested history”.

As someone that grew up inundated by visuals — majority American-produced, such as in Hollywood movies — of the “Vietnam War”, Yen is conflicted by the discord between what such imagery depicts and what she was taught in school about the “resistance war against the US”: “What is historical truth? What is authenticity? These questions grew bigger as I started working in photojournalism, and compelled me to explore different possibilities of history.”

Yen began by “photographing what is most visible to her” — war artefacts in Ho Chi Minh City: “You don’t even need to go to the museum to see American war planes, Vietnamese tanks or cannons. They are everywhere in most big cities and provinces in Vietnam. As Vietnamese we’ve normalised their presence and never really question what they mean, why they are here, their functions and how they actually affect us.”

For Yen, these artefacts “constantly remind her of our past. They are war trophies, telling our national story. Their presence is very intimidating but though they are so visible, there are many gaps in Vietnamese history we don’t address, such as generational trauma.” Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism and Allison Landsberg’s concept of prosthetic memory — ”the memorisation of events we did not experience but have absorbed through multiple media such as going to the cinema, reading books, watching television…and accumulated and formed into our history” have influenced her work on this project.

“Like prosthetic limbs, these war artefacts seem to be there to replace or cover the wounds and scars Vietnam has experienced, which we don’t talk about. I am intentionally trying to create meaning with my images in this series. As a photographer I’m aware that images are one-dimensional, compared to say film which is a series of images that usually gives more information and peripheral information on the subject matter. With single images, we don’t usually question the story behind them and why the photographer decided to photograph them that way. This pattern is similar to how we are taught history: we are given knowledge by a supposed agent of authority and we just take it in without questioning.”

Yen is also interested in “blurring the lines between fact and fiction” and has incorporated images “from domestic settings, including of my family and of my encounters”. Included in Alternative Imaginaries are fragments of photographs of her grandmother, whom she considers a “symbol of history” who has “been through both wars in Vietnam, the French occupation and the American war in Vietnam. She has seen so much and I know so little. This kind of relationship we younger generations have with history is also common within Vietnamese family dynamics because we don’t talk about our pain and the past. As a country, our mentality is to move on, rather than discussing how the past affects us even these days.”

Yen Duong included portraits of her grandmother, whom she considers a “symbol of history”, in “Alternative Imaginaries”.

To foster these kinds of connections between the historical and the contemporary, Yen has included “images of the modern day Vietnamese landscape”. One example is a photograph of a factory in central Vietnam that is linked to one of the country’s biggest environmental disasters in 2016, which led to mass fish deaths and major public health crises for local populations, but whose coverage was heavily censored. By juxtaposing it with the other images in her series, Yen raises the question of “how we ended up from a country that fought against imperialism to one that embraces capitalistic centuries and industrial development, and is repeating the act of censoring our history”.

“What happens when very conflicted versions of history confront each other in the public space? I know very well that history is security and maintaining a collective and cohesive history is an attempt to maintain our national security. But while we are trying to reinforce our national narratives by building more memorials and museums, and making them bigger, I think we are also slowly forgetting it. The essence of my work focuses on this triangle: collective memory, how it connects with our private history, and how I as a member of the younger generation respond to this.”

Women in Film & Photography 2021 runs till 19 Dec, with exhibitions in Objectifs’ Chapel and Lower Galleries, weekly online artist talks, a curator and artist-led tour, and two short film screenings at The Projector. Visit our website for full details and to register / purchase tickets.