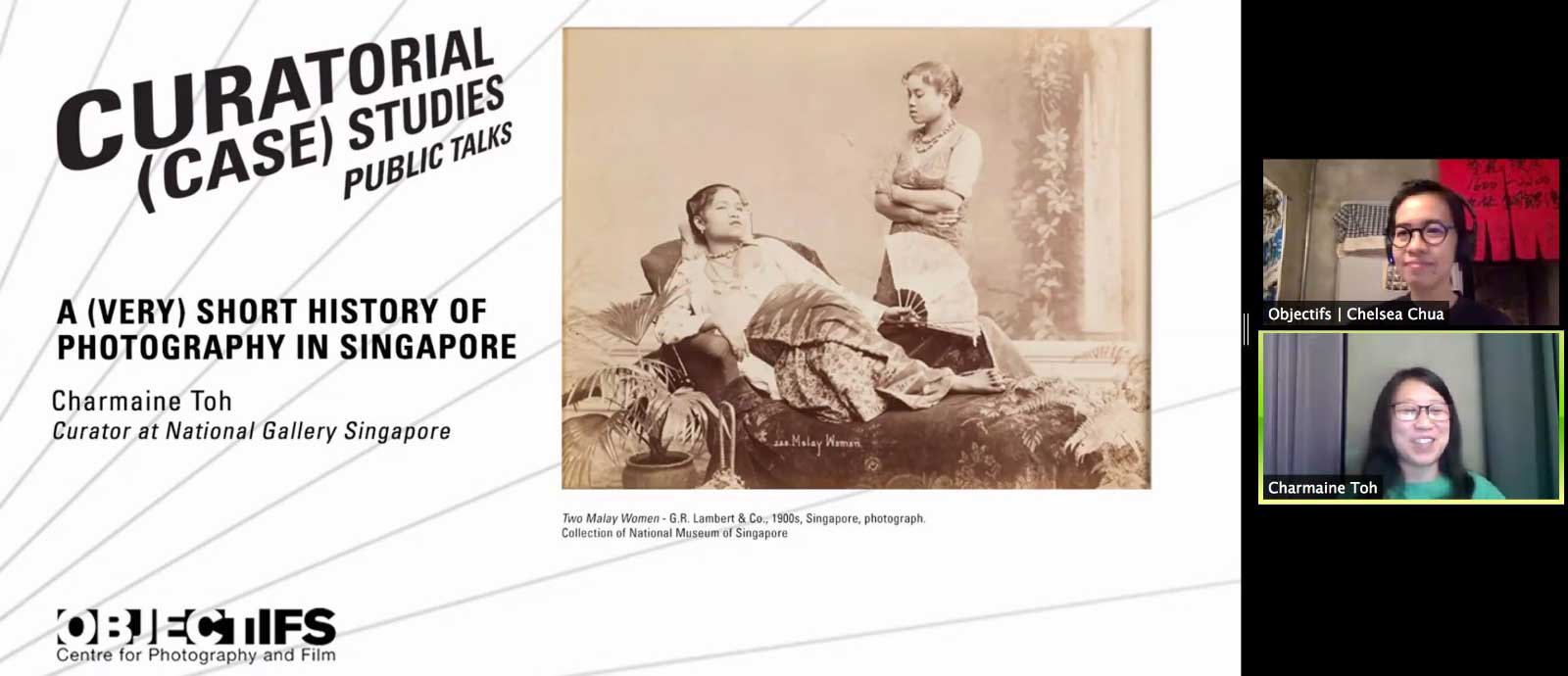

A talk by Charmaine Toh

Curatorial (Case) Studies is a programme by Objectifs that aims to bolster discussions around curating image-based work. As part of the programme in Nov-Dec 2020, a series of public talks addressed ways of looking at and understanding photography and film in Singapore and Southeast Asia, through the eyes of key practitioners, curators and writers.

Charmaine Toh, curator at National Gallery Singapore, spoke about the history of photography in Singapore. She prefaced the talk by saying that “Any history of photography is complicated because photography is essentially an interdisciplinary area of study. Since its invention, photography has played multiple and overlapping roles in art and science. The study of photography is a complex one, especially with its relationship to art.

The arrival of photography in Singapore

Charmaine took a straightforward chronological approach to the history of photography in Singapore. She began with the oldest surviving photographic image of Singapore, a daguerreotype by Jules Itier, which marked the presence of travelling European making daguerreotypes on their travels in Southeast Asia.

During these early days, Charmaine recounts that “photography played a huge role in visualising the world and that included Asia and Singapore. In fact, Singapore was a centre of photography. So due to its status as a port of call, many photographers stop in Singapore and many studios also set up a branch here.”

This eventually led to the establishment of photo studios such as, G.R. Lambert & Co., which was in business from 1867 to 1918. They and other photo studios of the period sold postcards of photographic images of Singapore as souvenirs to a mostly European clientele. These images consisted mostly of views (landscapes) and types (people). At one point, G.R. Lambert & Co. sold 250,000 postcards in a year, a tremendous volume for the time.

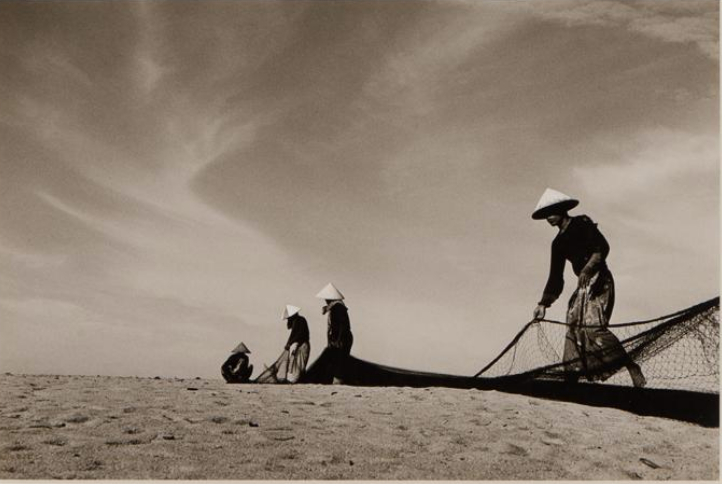

Charmaine discussed the potential of such photographs to present a kind of imperial, Victorian gaze. “The picturesque landscape was typically found on the banks of the Singapore river, and in the growing city, culture was seen in the Victorian edifices, the white boulevards and the plantations, while nature lurked in the tropical forest just outside the city and in the sea that surrounded the island, and in the figure of the native often found in traditional dress…

Such photographs, I argue, celebrate the civilising and modernising processes introduced by the British. Keeping in mind that such photographs were made primarily for a European audience, these landscapes were a specific vision of Singapore that used elements of the pictureque as present a naturalised view of British Singapore.”

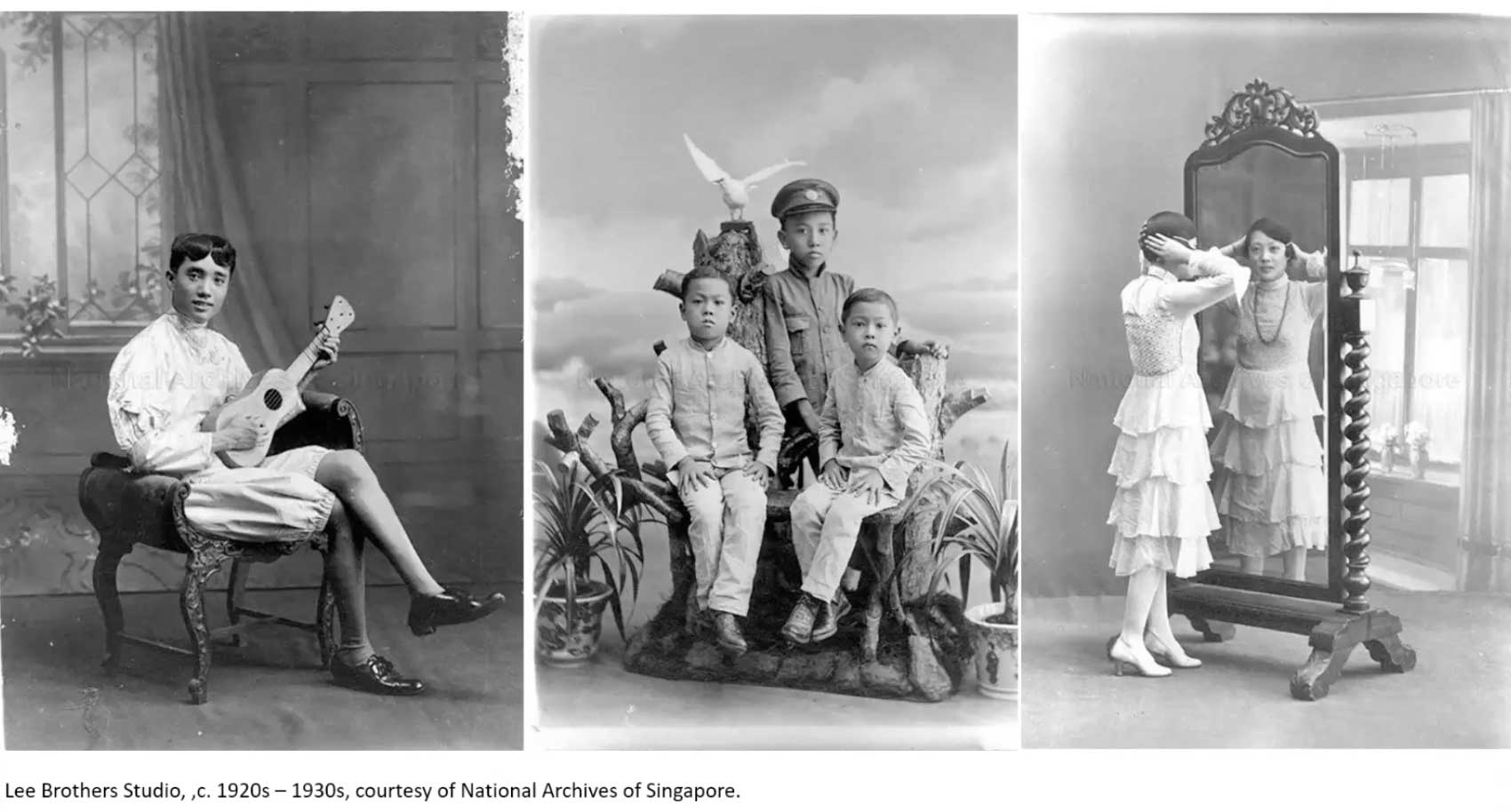

By the 1890s, Singapore saw the emergence of many photo studios set up by Chinese photographers who came to Southeast Asia in the 19th century, many escaping the Taiping Rebellion in southeast China. These studios providing commercial portraiture services, which continued to be in demand by the rich Straits Chinese families, and ushered in a new era of studio photography, which Charmaine feels is “often overlooked in photo history, particularly in this region. But it has played a very important role in bringing photography to the masses. And its significance I think, also lies in the way it allows individuals and families to imagine themselves.”

The emergence of amateur photographers

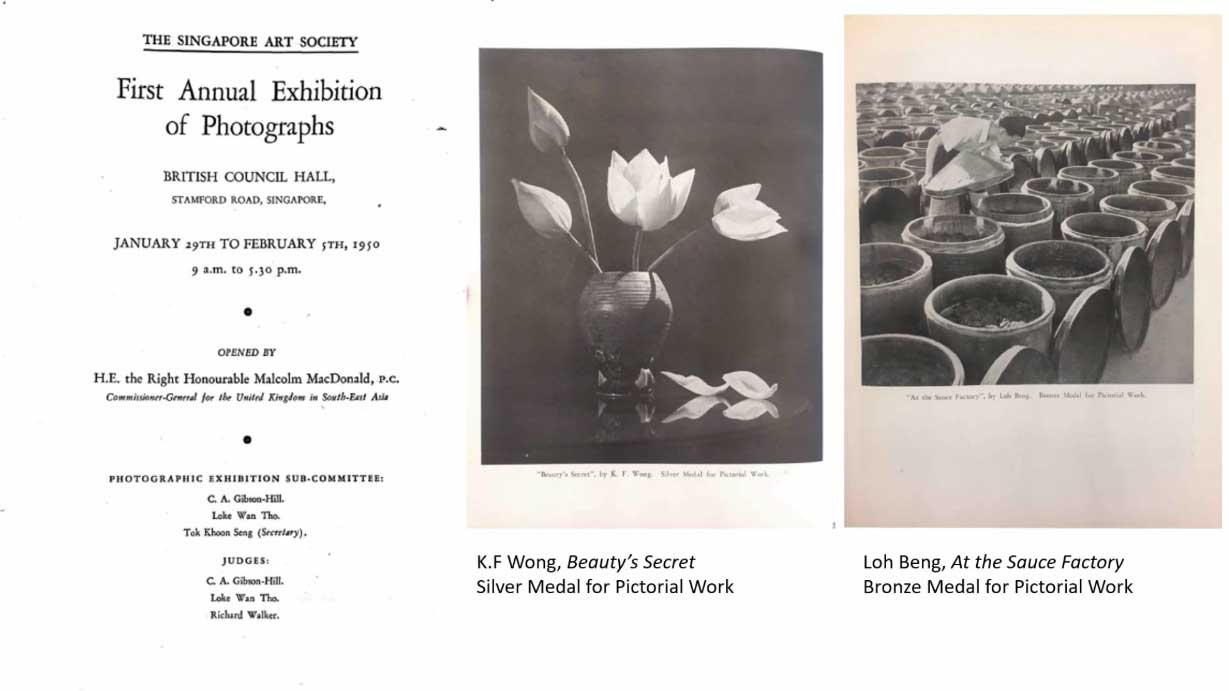

As photography grew in popularity, 1921 saw Japanese photographers start the Singapore Camera Club, while the Malayan camera club was formed in Kuala Lumpur.

“These two clubs were extremely significant for being the first signs of local photographers consciously privileging aesthetics, a key development in photographic practice in Singapore. They organised the earliest art photography exhibitions. The club and exhibitions also provide clear evidence of the presence of European style pictorialism in Singapore.”

Photography exhibitions were immensely popular; 40,000 people visited the Malaya-Borneo Exhibition on the first day and newspaper reports note that the photography exhibition was very popular.

The development of photography unfortunately halted during the Japanese invasion of Singapore from 1942 to 1945. This also resulted in the destruction of many prints, representing a great loss in our pictorial history.

Courtesy of Charmaine Toh

Post World War II, Singaporean interest in photography resumed and grew exponentially over the next 20 years. Photo clubs and photo exhibitions proliferated in Singapore from the 1950s to the 1970s; many Singapore photographers also regularly sent their prints to international salons in London as well as in other parts of Europe, America, Australia and Asia, resulting in the circulation of an immense number of photographs from Singapore. These clubs were styled after similar clubs and salons in London, the popularity of which peaked in the 1960s.

Many amateur photographers during the period (including practitioners such as Lui Hock Seng and Lim Kwong Ling) eagerly sought opportunities to improve their craft; this translated to a dramatic improvement in quality just over a few years, as Charmaine detailed through an examination of exhibition catalogues over this period.

Charmaine went on to the cite the work of Wu Peng Seng and Tan Lip Seng. Of Wu Peng Seng: “He had a very strong sense of design and pattern, with great sensitivity to light and shape to strict composition and framing. Peng Seng consistently made work that I think tread the line between decorative and illustrative, which was very much in keeping with this group of photographers commitment to beauty.”

The younger of the two, Tan’s highly individualistic style was marked by photo montage and colour derivation technique, which was the result of constant experimentation.

“I actually like to show their works in my talks on photography from this period, because a lot of people assume that photos from the 60s and 70s in Singapore were traditionally black and white prints of kampungs and labourers. But there were also photographers who were very experimental.”

Turning towards the contemporary

The enthusiasm around the practice of pictorial or what was more commonly known as salon photography had largely petered out by the late 1970s. While photographers such as Kouo Shang-Wei and Chua Soo Bin established significant careers in the 1980s, art photography by that time had started turning towards the contemporary, as “photography became a widely accepted medium used by artists who did not necessarily identify as photographers. Photography also started to take on significance with respect to performance art, as it was the main way such work was documented.”

In her discussion of contemporary photographic practice, Charmaine citied the work of Chow Chee Yong, Darren Soh, Wei Leng Tay and Robert Zhao, chosen for their commitment to the medium. Their works play with the photographic form and conceptual ideas around photography. Of particular interest was Robert’s win in the 2009 UOB Painting of the Year Award, which ignited a discussion in mainstream media around whether photography could be considered ‘art’. “I thought that it was ridiculous to have this debate come full circle in 2009; just following the history from the 30s, the 50s, the 60s, you can see that the discussion has gone backwards and started questioning the status and role of photography again.”

Find out more about the early history of photography in Singapore:

Amek Gambar – Taking Pictures: Peranakans and Photography, ed. Peter Lee

A Librarian’s World: Daguerreotypes to Dry Plates – Photography in 19th Century Singapore, a talk by Janice Loo

A vision of the past : a history of early photography in Singapore and Malaya : the photographs of G.R. Lambert & Co., 1880-1910 / by John Falconer ; [edited by Gretchen Liu]

For recaps of other talks presented as part of Curatorial (Case) Studies:

- Manit Sriwanichpoom: Image-maker/Curator by Manit Sriwanichpoom

- A History of Cinematic Exhibitions in Southeast Asia by May Adadol Ingawanij