Liao Jiekai and Yanyun Chen in conversation

The first Objectifs Film Club session of 2021 featured Singaporean filmmaker Liao Jiekai in conversation with artist Yanyun Chen about their collaboration on The Drawing Room & Episodes from Art Studio, a short film inspired by the novel Art Studio by the late Singaporean writer Yeng Pway Ngon. The conversation has been edited for brevity.

Liao Jiekai: The short film was conceived in late 2014 when I did a residency in Aomori in Northern Japan. Art Studio by Yeng Pway Ngon was the only book I brought with me. I thought I’d spend the whole three months reading it but I finished it in two weeks. I was very captivated by the story and the characters. It’s a very cinematic text.

When I returned to Singapore, I was introduced to the author to discuss adapting Art Studio into a film. Art Studio traverses many different countries across decades. The story brings you from Singapore, to Hong Kong, to India, to Europe…it’s a really big story.

I was originally very drawn to the text because of the drawing component. Coming from a visual arts background when I was younger, I relate a lot to the scenes with artists drawing and discussing the meaning of drawing. I thought I’d also make a short documentary about drawing as a way to enter or jumpstart the very ambitious [feature film] project. That’s how The Drawing Room and Episodes from Art Studio came about.

I was able to begin this project when I received a grant from The Arts House’s New Word Order programme calling for artists to adapt Singapore literature into another art form. I wanted to work with another artist who would be live drawing and approached Yanyun whom I met a few years earlier. In contemporary art today, it’s quite rare for an artist to still focus on representative work and in a very rigorous way. So I was very intrigued by Yanyun’s practice.

Yanyun Chen: I was studying in a very classical fine art atelier in Sweden for one year and came back to Singapore in 2014. I had a little studio in Goodman Arts Centre where I was doing a lot of drawings but I didn’t have many opportunities to draw models as it was too expensive to hire them and I was very broke then. In 2015 I organised Studying Life, a tiny exhibition of works by three artists: Alvin Mark Tan, Sara Chong and myself who had all trained in classical ateliers. When Jiekai reached out, I invited him to my show.

At that point I hadn’t read Art Studio. I was surprised there was an author writing about life drawing. It turns out it wasn’t fictional, but based on his own experiences with life drawing which, like Jiekai says, was at that point quite an outdated way of learning how to draw. Very few schools were still promoting it avidly and it was seen like classical training, a bit outdated. It found ground only in animation studios. In Singapore, before LASALLE embraced life drawing, there were artists’ groups already doing so. Many of these artists were Western-trained or had travelled to Europe, America, Australia even. Life drawing was just not found in Asian art curriculum.

Jiekai: Especially in education, figure drawing will always have some kind of role. Many teachers believe it is an important aspect of art education. It’s still a very institutionalised aspect of art education in many schools around the world.

Yanyun: It’s also a safe space for models to work in. The goal and the task of a session is very clear. Modelling for artists in an educational institution becomes safer than in independent spaces sometimes. Live drawing is still around. It hasn’t disappeared but weaves in and out of core curricula.

I told Jiekai about my time in Sweden and how with this kind of training you spend 72 hours with a model, you do the same drawing for six weeks. It’s a very long and slow, patient sort of process. I asked if he was sure he wanted to film me drawing because it’s not very interesting. At that point, I hadn’t been drawing the figure for quite a while, just because I didn’t have opportunities to, so I was very excited that someone would put in a bit of cash to hire a model. I was very excited, thinking, Yeah, I get to draw again!

Jiekai: After I read the book, my interest was not only in figurative drawing but in the model. In Art Studio the model is a really shy young boy who is tricked into becoming one by his best friend. There’s a lot of personality written into this model. The model is no longer just an object that we draw, but is a person. It’s the same when I work on other films.

I use the camera to look at and observe people. I hope that when I see them and film a face, there is something behind the facade that we are able to probe and explore to deepen our relationship with or understanding of this particular person.

I see a lot of parallels between this process and Yanyun’s practice. I did live drawing when I was a student and didn’t think very much of it. But when Yanyun told me about her experiences in Sweden, it really drew me to the process.

She shared how she was drawing a lady who didn’t know that she was pregnant. And over the weeks the artists were the ones who started to see the change in the model’s body. That is so magical. When you spend a long time one on one with another person you really start to understand them in a different way. And drawing is just another process to understanding another person, whether it is a model, or someone else. So I was interested in this duration. We spent 48 hours together: what can we know or understand?

Yanyun mentioned it could be boring, but I myself was surprised that I could always find something new to look at. I wasn’t only looking at the model, but also at Yanyun working. It wasn’t mundane at all, to me. I could see changes: the light, the way the sun came into the room, how the model was feeling that particular day which changed the way she stood or moved slightly. In these very seemingly mundane situations, there was a complexity within the details that interested me. So I wouldn’t say I adapted Art Studio; it was mostly inspired by. Although I use the characters in Mr Yeng’s book, I took a lot of liberties in changing the story and adding context.

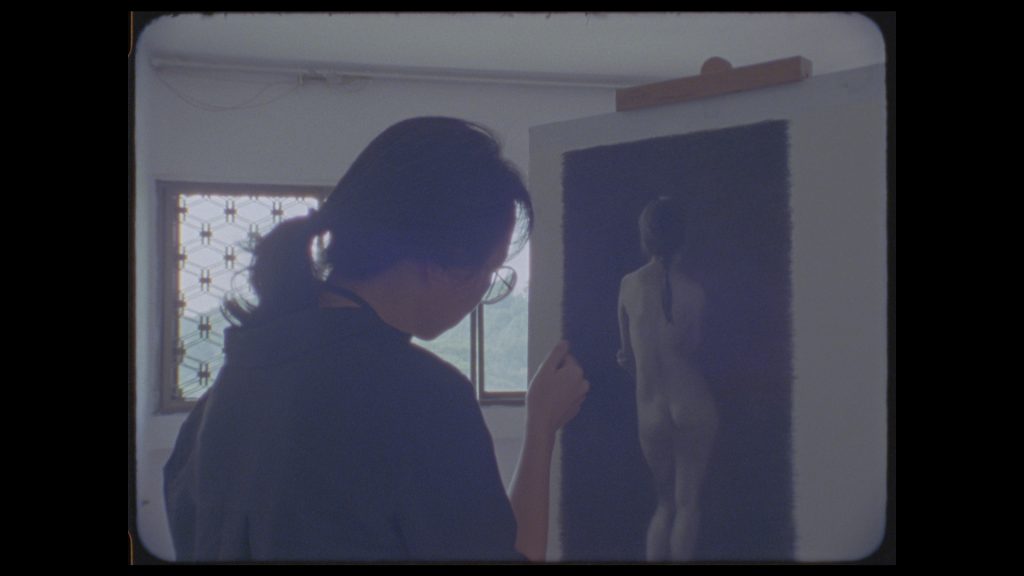

Yanyun: Jiekai didn’t direct me. We found a model who was okay to be filmed, she shared with us what she was comfortable with and not, and we discussed how to set up the space. We filmed in the risograph printers Knuckles & Notch’s old studio in the old Normanton Park. It was a very strange old room with a carpeted floor and wasn’t very big. Jiekai had a very limited supply of film and was rationing it out. When I get into the mode of drawing, I just draw. I was aware that Jiekai was filming, the camera was on, there was a sound person, but I have structured stages in my process of drawing that I pretty much just followed.

Jiekai: I had to be very economical because I had very limited film stock. I had only about half a tin of film for each session, which is five and a half minutes of footage. So I was very aware of how much more I could do each time. On some days, I’d see something really interesting and shoot more and on other days I’d do a bit less. Such parameters helped me think about what I should be capturing.

Audience Member: The drawing is very realistic, and the camera captures things realistically, like two model realisms facing each other.

Yanyun: It’s a very acute observation. I was also very intrigued by this. What do we mean by capturing a subject?

When you’re drawing, you’re not just copying what you see, you’re choosing what you see and choosing what you show in the drawing. It’s quite similar in the filmmaking process, especially since there’s this ability to cut between durations. I think my drawings are like a compression of those 48 hours of being with this person. The film is not really a compression. The edit creates a different narrative.

Jiekai: I decide what the camera is looking at, at any one particular point of time. We talk a lot about documentaries being films that depict reality, but I beg to differ. The moment you put a camera in a room, people change, they don’t behave the way they would if they were alone. Because I was shooting on film, and people could hear the winding of the camera whenever I pressed record. Everybody knew I was recording. It’s not like shooting digitally where you can just press a button, you can put tape over the light, nobody knows when you’re actually recording. With film, people are hyper aware of when they are being recorded, and that changes their behaviour. So I will say that it is not realistic like a situation where Yanyun would be alone in a studio making a drawing. It’s a different reality.

Audience Member: Why did you still choose to shoot in celluloid instead of in a digital format, where your role as cameraman could be more invisible?

Jiekai: The subject being aware of you isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I think they will always be aware that they are being filmed unless you are secretly filming someone from very far away, or they’re captured on a security camera, etc. The tension, how that awareness changes a person, can be interesting. It’s part of the equation when you make a film. I’m not very fond of filming people secretly. Sometimes I do that in the context of fiction filmmaking where you start rolling the camera before the actors know it is. But still, the actors already know that we are in a situation where we are making a movie, which itself transforms the situation.

Last year, I made a film with a dancer also shot on celluloid and I was using a loud Bolex winding camera. The dancer was hyper aware of whenever I was filming her. The winding camera can only shoot a maximum of 30 seconds on one take, which annoyed her, because there is a rhythm to her dancing. She knew I wouldn’t be able to film the entirety of her movement and that I wouldn’t be able to capture parts of her choreography. I did tell her before filming about this parameter we had to work with and she reconciled with it when she saw the footage.

Puiyee: You’ve both been live models before.

Yanyun: I was still in secondary school and I wasn’t nude, but sat for a portrait. My seniors had an exam assignment to draw a portrait of a person in three hours and I got roped in to sit there for three hours, not really knowing what I was getting myself into. It’s really hard to stay still for three hours. It was boring but also quite interesting because you start finding things to look at though you can’t move or turn your head or look anywhere else.

Jiekai: I was also a live model before as a kid. It wasn’t the most comfortable staying still especially as a kid and a very uncanny experience when you saw the drawings other children had done of you. Some of them would be very grotesque!

The filming process became very meditative for the artist and for me and it was relaxing partly because we kept the team very small: Yanyun, the model, me and a sound recordist who’s also a friend. I enjoy working like that. It helps me focus more. We weren’t rushing. We were not chasing the time but just quietly looking for moments to appear before me and then very quickly capturing them.

Yanyun: I get nervous in front of cameras but Jiekai gave me such a simple task: here’s a month of time, you just need to draw. That really helped me ignore that there was a camera around. All I did was walk forwards and backwards towards the easel, back and forth. The model was just there. Jiekai would move around in the space.

One of the pleasures of life drawing is that things are living, light is changing, people are breathing, something is always something happening, but it’s never the same. My drawings tend to be very representational; they look like still photographs. But it’s actually not still at all. Everything is moving. I gain a lot of pleasure in the fact that it’s always changing.

Puiyee: Was the final short film very different from what you expected?

Yanyun: I was very curious. The scenes where the close ups that follow the contours of my finger alongside the contours of the drawing were very nice shots, they felt like you’re looking, they felt like how I see elements of someone’s body where you spend a lot of time with something very small. And it’s very beautiful in capturing the light. I was definitely surprised. I didn’t realise how you can you can shoot so many things.

Puiyee: There is a scene in the short film where the narrator discusses the ideals him and his close friends have about anti communism, which is juxtaposed with visuals of the setting up of the National Gallery Singapore, and we see works by Singapore artists like Chua Mia Tee. Why did you choose this particular text to go with this scene?

Jiekai: The scripts for both the feature film adaptation and this short film were co-written with my creative collaborator Daniel Hui who is also part of 13 Little Pictures. We discussed how when we read the book, we started to imagine how we could look at the artists mentioned: who they are, how we look at their works from a historical perspective, from our understanding of the different art movements and how we could place them in the historical trajectory of Singapore art.

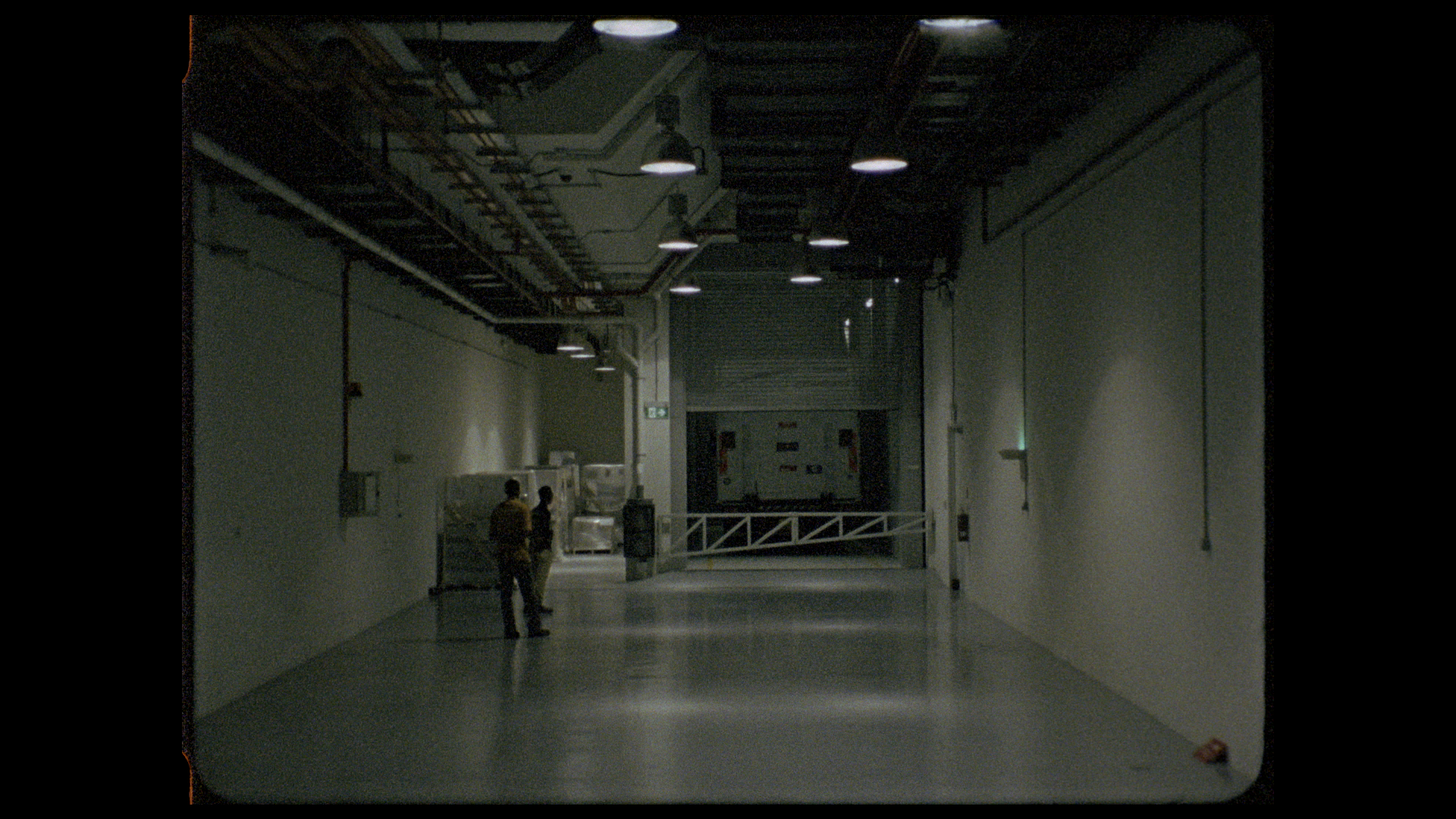

The National Gallery Singapore was just about to open and I just intuitively felt that I needed to go and film it specifically before it opened to the public to get a sense of how they select the paintings, what they use to hang them on the walls — they are literally building a narrative for the museum goers to follow. I was mostly an observer; I brought my camera just one afternoon. I had permission to follow the truck that transported the paintings all the way into the loading bay and as people carried the paintings up. I chose this particular gallery which featured the works of The Equator Art Society because they seemed to have the closest relationship with the painters mentioned in Art Studio. I filmed the images first, I didn’t really have a script. After that, we wrote the voiceover that you hear in the film.

Puiyee: Yanyun’s drawing was also exhibited with a different excerpt from Jiekai’s film as part of Spirit of Place, a 2016 group show at the Esplanade. How did that come about?

Jiekai: When editing The Drawing Room and Episodes from Art Studio, I had mentioned to Sam I-Shan, who was then the Esplanade’s visual arts curator, that I was interested in making an installation version of this work. I was aware that in an exhibition most audience members wouldn’t spend 20 to 25 minutes watching something. With that in mind, I thought of taking out the story from the film, and called it The Drawing Room [watch some documentation here]. I took out Episodes from Art Studio. I removed our studio drawing process. I created an installation juxtaposing film photographs I had taken of figures and sculptures in museums, parks and cemeteries in Italy and France next to Yanyun’s drawing.

Puiyee: How was the late Yeng Pway Ngon’s response to the film?

Jiekai: He didn’t attend the screening due to his health but I showed it to him on my laptop in a coffee shop where we usually met to chat. He usually didn’t comment much. He gave me a lot of liberty. He didn’t give me any feedback. So I don’t really know what he thought about it.

Audience Member: What was the process like adapting the book for screen, compared to writing original screenplays?

Jiekai: It was my first time adapting a text from a book. I was very lucky that Mr. Yeng was very hands off. Whenever I asked him about his opinion about changes I wanted to make, he didn’t really want to say anything because he didn’t want to influence my interpretation of his work. He just wanted to let other artists make their own interpretations of his texts.

Usually, when I work on my own scripts, they’re from my own personal experience so I have something to start from, but I find it hard to write if it’s not personal. I’m not a very good writer so having a base text to begin with and not starting from a completely blank slate really helped me to imagine or take a scenario and move it into different directions.

Yanyun: What do you think about the film now five and a half years later?

Jiekai: I’ve always found it very difficult to like my own films. A former lecturer of mine once said it’s the unfortunate fate of filmmakers and artists that our words are made for other people, not for ourselves. We cannot see the work in the same way as the regular audience; we will always see what it could have been. But life is what actually makes a film interesting, because we cannot predict how people will behave, how the weather will behave, what new things the project will bring you when you start filming it. That disconnect between your imagination and the work itself will always plague you. I only sit through my film screenings once or twice and then I just don’t watch it anymore. Once I make a film it doesn’t belong to me any more, it belongs to the audience. I just move on and do the next one. I don’t think about it.

Audience Member: Are there cultural and societal factors and other aesthetic movements that might have contributed to the resurgence of the figurative in Singapore?

Yanyun: Currently, people spend a lot on conceptual works that are non-representational to the furthest extent you can think of. Art scenes are constantly looking for novelty so they will always respond to the counter. The movement towards the conceptual, the contemporary, the intangible — which are very beautiful things also — has opened a little bit of space for the figurative. There’s also this embrace of postcolonial discourse and of finding non Western approaches to understanding art and culture.

Often the power to do so comes from using a trope that has been established and turning it to one’s own. Artists who would otherwise have not found space to exhibit previously have embraced figurative oil paintings as one of their ways to get their voices heard. They want to rethink what it means to present themselves. They want to create their own identities. They want to use their bodies to say something. That way, they don’t end up borrowing someone else’s voice, they are purely responsible for the body that they use, which is their own.

Of course, some artists are still reluctant to embrace more figurative representational forms. Not every artist wants to deal with bodies. It’s also difficult to deal with bodies; the way we talk about and present them is very problematic at times. But every artist finds ways to tell their stories.

The Drawing Room & Episodes from Art Studio and Jiekai’s other films, along with with other short films by Southeast Asian filmmakers, are available to rent on the Objectifs Film Library. You can also read our past Film Club recaps here.