Queer Asian womxn filmmakers on their LGBTQ+ Stories

Objectifs’ sixth Women in Film & Photography showcase included two short film programmes which screened at The Projector on 4 Dec 2021. Remnants and Reflections, curated by Darunee Terdtoontaveedej, presented five short films by Asian filmmakers who identify as female, queer, non-binary womxn.

Read on for a recap of the live Q&A session with three of them — Dorothy Chen, Kaori Oda and Pom Bunsermvicha — in conversation with Leong Puiyee (Objectifs), that followed the sold-out screening.

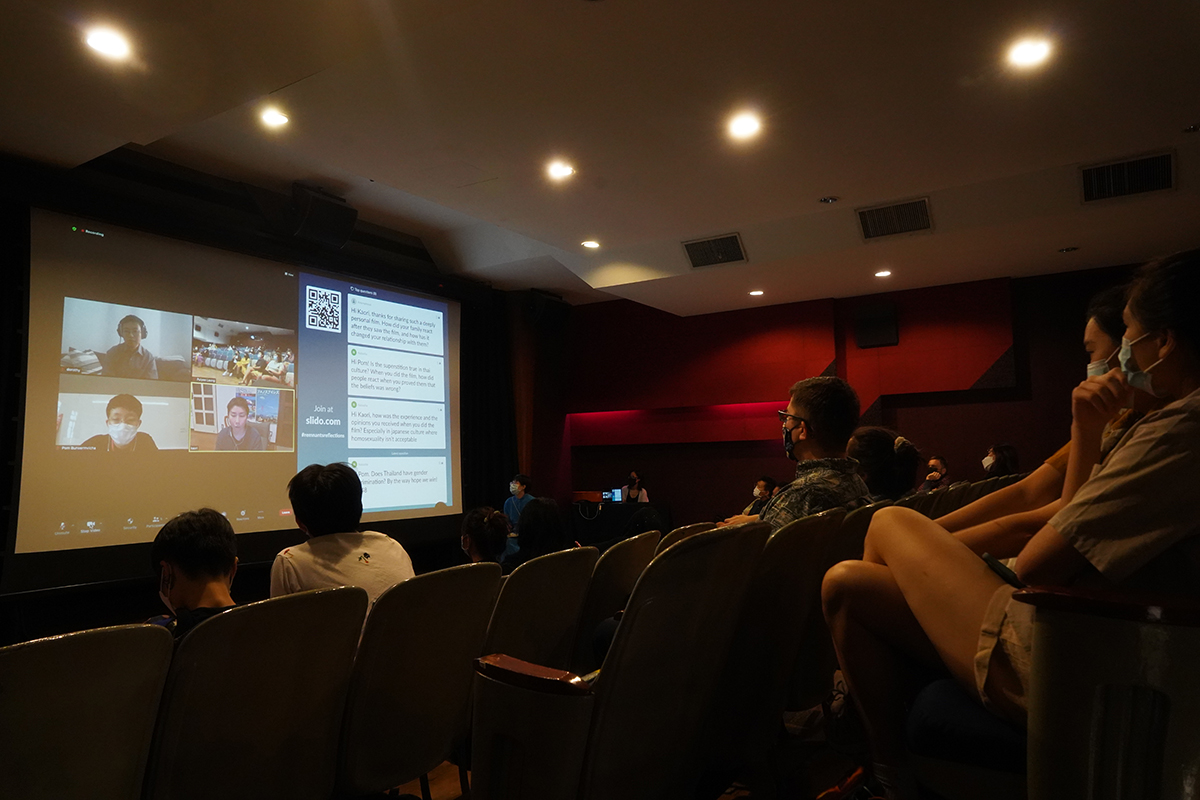

Virtual Q&A with (anti-clockwise from top left) filmmakers Dorothy Cheung, Pom Bunsermvicha and Kaori Oda, moderated by Leong Puiyee (Objectifs)

Dorothy Cheung – A Room of Oblivion

Leong Puiyee: Dorothy, what prompted you to create your short film A Room of Oblivion?

Dorothy Cheung: I was working on a graduation project about the colonial archive of Hong Kong. It was very public: about history, people and politics. While working on that, I also started looking at what personal history is, and what personal archives are. I started looking in my personal archives [to understand] how history affects us in the present, and made this film.

From “A Room of Oblivion” by Dorothy Cheung

Puiyee: You mention in your film that you lost some footage. Did you want to meld your personal memories with the research you mentioned?

Dorothy: The research was more theoretical. This is a much more personal take. At the point of making this film, I hadn’t talked to this ex-partner for nine or 10 years. So it was a way for me to try to resolve the past, just for myself.

Pom Bunsermvicha – Lemongrass Girl

Puiyee: Pom, we have a superstition in Singapore similar to the one in Lemongrass Girl. When we do outdoor events, we have to plant some chilli. I don’t know if a girl must do it, but definitely a virgin. When I watched your film, I wondered about these Southeast Asian connections. You did a lot of research and had many conversations about the superstition. Did you ever find out why particularly lemongrass, and why it has to be upside down?

Pom Bunsermvicha: That’s a very good question. I’ve never actually thought about why lemongrass. But it has to be upside down because in the past, we’d ask the gods for rain [and plant the lemongrass right side up] so that crops would grow . So [for our purposes, when we don’t want it to rain], it has to be planted upside down like it’s “mocking” the sky, and the gods would not grant us rain.

This tradition of planting the lemongrass upside down has been around for hundreds of years. But the insistence on women performing it only came much later. In our culture, gender is huge and a virgin woman is believed to be the most pure entity. So in order to have the best chance of preventing rain, we must ask a virgin woman to perform it. Beyond tradition, it has become a kind of virginity test.

Puiyee: Meaning that if a man wants to know whether his bride is a virgin, this “test” is performed?

Pom: Yes, this happens in the countryside. It’s something very sacred that people believe in – asking a man’s fiancee to go plant the lemongrass. If it rains, it might mean she is not pure any more.

Puiyee: And the wedding might be called off!

Audience Member: How did people react when it’s proved in the film that the superstition is false?

Pom: I made Lemongrass Girl on an actual film set. The prominent female Thai director Anocha Suwichakornpong was making her fourth feature film. We had conversations with a community of people that believes in what we do. We spoke about being women and about harassment and bullying on film sets. Anocha collected different stories and wrote the script.

“Lemongrass Girl” was shot on the film set of prominent Thai director Anocha Suwichakornpong’s fourth feature film.

So everyone on the film set was also performing in Lemongrass Girl. I didn’t have to explain anything as it was so common to them. Some of them had also been the lemongrass girl. But Piano, who plays the production manager, hadn’t before and it was an interesting experience for her.

Puiyee: Has she seen the film? What was her reaction?

Pom: Piano has actually not yet seen the film. She’s actually in the room with me!

Piano: It was quite tiring both working as the production manager for Anocha’s film and acting / being documented as a lemongrass girl for Pom’s film. So I didn’t focus on when Pom was shooting me. When planting the lemongrass, I just tried to pray for the gods to stop the rain. I felt uncomfortable because I tried to believe it was my duty to pray for everyone’s safety during the production.

Kaori Oda – Thus a Noise Speaks

Puiyee: Kaori, there are so many layers to your film Thus a Noise Speaks. How did you feel while filming it, re-enacting the process of coming out to your family?

Kaori Oda: It was very tough but I knew I had to do it, to somehow try and find a way to communicate with my family. And for me, it was through filmmaking. But it was tough to ask my family to say “it’s disgusting” or that they could not accept me. It was also tough to see them getting hurt by saying such things to me. I almost gave up in the middle of the shoot but my sister got angry and said it would’ve been better not to start, if we didn’t finish the film! That cheered me up and we somehow finished making it.

Puiyee: When you explained to your family that you wanted to recreate everything, how did they respond?

Kaori: They were confused, of course. They had no idea what I wanted to do with them, and I didn’t either. I just knew I had to do something. But it was my bad to use their feelings in that I knew they could not refuse me [again]. They knew I would be more upset if they refused.

Puiyee: You’ve mentioned in some interviews how you realised the camera can be a very violent tool, and that you were worried you may have hurt your family.

Kaori: It was my first time operating the camera. I didn’t know then what it could do with the people in front of it. I was also in front of the camera but I had the power to also be behind it. I could edit, manipulate what the film could be. I could also determine what the truth was in this documentary. I was still learning with this film how to use the camera consciously. But I also believe this was the only way for me at the time to try to discuss with them what we couldn’t talk about.

Audience Member: Kaori, how has your relationship with your family changed after making this film?

Kaori: The film screened at an arthouse cinema in my hometown, Osaka. I invited my family to watch. My dad said it’s the best film I’ve made so far. My mother called me after she watched. She didn’t say much but I could feel that there was so much in her silence, so much going on inside. I now have a good relationship with my family. I can speak with them about anything.

Audience Q&A

Audience Member: Gender and LGBTQ+ perspectives have evolved but there are some persisting problems that your films have covered. Can you comment on some of them?

Dorothy: My film doesn’t directly discuss LGBTQ rights. It’s more about how an individual queer person can see their own history. I want to question if our history always has to be a tool for political or LGBTQ rights. Can they be just memories? Maybe it’s possible that we sometimes forget them or make mistakes. We don’t have to be model LGBTQ persons who always do everything right and remember all our histories.

Pom: I’m a queer filmmaker but my film isn’t about being queer. It’s about being a woman. Gender inequality is still huge in Thailand: in our language, culture, the way that everything functions. It affects me and my peers in the filmmaking community. Though perspectives have evolved the lemongrass girl superstition was weird to even make a film about as we’re all so used to it.

But it was important to question already set norms, beliefs and practices. It’s very easy to say I don’t agree with it but actually making a film about it allowed me to understand the history and how it’s evolved and to engage with it enough to understand how it can affect someone else, or somebody on a film set. Even hearing Piano share how she felt uncomfortable performing this role as an actress, it’s very interesting to think about how superstitions and what we do every day affects all of us.

Kaori: I think the situation for LGBTQ people is improving. There’s been a big difference in the last 10 years. I can bring my partner to my parents’ home now. It’s not only because I came out but because they are more used now to seeing people like me on TV, in cinema. They [understand] that it is normal, okay to be who we are. Previously, they thought it wasn’t okay to [fall outside of] a clear gender binary. I hope the situation will continue to improve, with programmes like this one.

Puiyee: Does each of you have any last words for the audience?

Dorothy: I was very moved by the other films in the programme. Though my film is about forgetting, it’s important to make meaning of your memories, whether they’re very sad, painful or happy ones.

Pom: I was completely taken by each film too. Kaori made her film 10 years ago and I’m curious to see the work she’s done since. Dorothy’s work is so brave and personal, and asks something beyond what we know. It’s great to be in this space and share our films with everyone. Thank you to Objectifs and Darunee for bringing us together. I hope we’ll have more such spaces in the future to discuss gender and sexuality.

Kaori: I love Dorothy and Pom’s films too. It’s so nice to have this kind of space during Covid-19, chatting with people and talking about my film from the perspective of being a sexual minority and thinking about gender.