Part of Stories That Matter 2020: Who Cares?

Objectifs’ annual Stories That Matter programme looks at critical issues and trends in non-fiction visual storytelling. The theme for our 2020 programme was Who Cares?, reflecting on how image-making and the act of looking are implicated in systems of care and responsibility, and how these systems are increasingly complicated by phenomena such as social media, surveillance and big data.

Objectifs presented a site-specific work by Hasan Elahi, an artist whose work examines issues of surveillance, citizenship, migration, transport and the challenges of borders and frontiers. Shroud, a large outdoor installation in our Courtyard, comprised thousands of images from Tracking Transience, Hasan’s ongoing project on self surveillance.

Due to Covid-19 travel restrictions, Hasan was unable to travel to Singapore for the programme. His artist talk was held on Zoom in September 2020. This recap presents some of the highlights from the online session moderated by Chelsea Chua, Programme Director at Objectifs.

After an erroneous tip called into law enforcement authorities in 2002, Hasan was subjected to an intensive six-month investigation by the United States’ Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI): “I spent six months going in and out telling them everything, every little detail, showing them exactly where I was.” The timestamps on his images became important in establishing his whereabouts with great specificity and to establish a timeline proving he couldn’t have been in certain spots at certain times. After his harrowing experience with the FBI, Hasan conceived Tracking Transience, and opened just about every aspect of his movements and activities to the public.

Hasan showed timestamped photographs from his past travels in Singapore. He said, “These images could really be anywhere, but they’re very specifically local spots. If you’ve eaten this fish, for example, it could only be from that one restaurant, because we know exactly how they do it there.”

“One of the first things I did after the FBI cleared me was that I flew to Singapore and stayed in the airport — a buffer zone — for four days and then flew back. Where was I for four days? If I died there, what would be my place of death? I hadn’t technically gone through customs and immigrations and entered Singapore. There’s a record of me leaving and re-entering the US but I was off the record for four days. The airport became a surrogate space for nowhere.”

On camouflage and hiding in plain sight

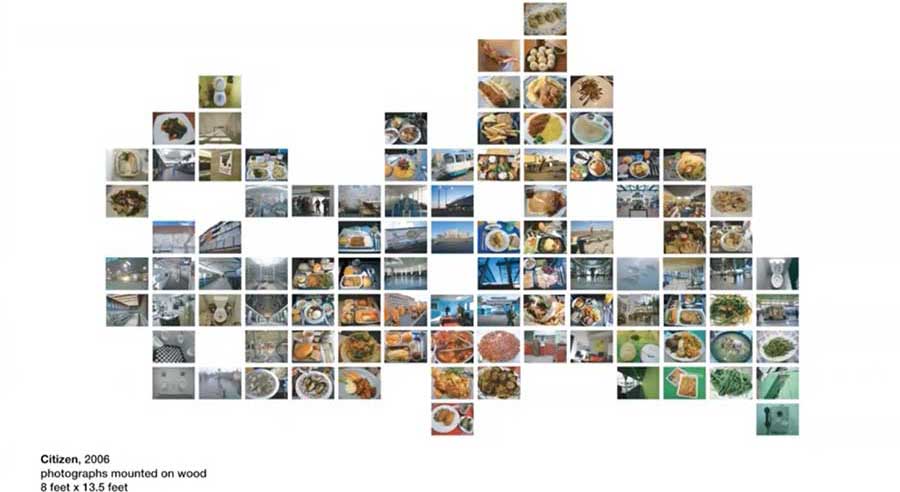

Hasan has repeatedly used and explored camouflage in his works, from Citizen (2008) to ERDL+ (2017). In ERDL+, we see the evolution of camouflage. Historically, camouflage was used so the body was indistinguishable by the enemy from the landscape. But now, the pattern is digitised.

“What is data camouflage, and what does it mean for our personal lives?

All of us are generating so much data. We can’t hide completely, because our data tracks are so extensive, but we could blur; we could literally be hiding in plain sight.

“My process of telling the FBI everything was also a form of defiance. By doing so, I basically decided to tell them almost nothing. In Shroud you’re looking at thousands and thousands of photographs to the point where they become camouflage, noise, texture from a distance”.

On expansion of territory — physical and digital

Hasan’s works also explore his interest in war and the expansion of territory. Peak v3 (2016) shows US government space surveillance, against the Hawaiian landscape, questioning the constant surveying of what seems like “nothing”.

“Every country identifies itself (.sg, .jp .au etc) on the Internet except the US, because it’s assumed if it doesn’t have a country domain, it’s American. There is a dominance of the digital space in addition to physical territory. It’s scary to think about, it’s problematic in a global space such as the Internet. It’s about the dominance of territory and the idea of warfare — whether it’s visible or takes place much more invisibly. The whole ‘war on terror’ got me caught up in all this. This is about war.”

There is a lot of political symbolism in Hasan’s works. Prism (2015) has 13 stripes which are iconic of the red and white stripes of the US flag. “When you look at the top it looks like any industrial or commercial building but it also depicts the rooftop of the NSA [National Security Agency]. We’re in the same business of collecting information, except they don’t like to share theirs and I do!”

“When you look at images, you see GPS details as well… Year after year, Google drives up and down every single street photographing it. They have archived every public space except where the law forbids it. Zoom has archived practically all domestic, internal space. Mathematically we can restitch all of these internal spaces together. When you look at “Frequent Locations” on your phone, it documents where exactly you were and how long you spent there. When you stitch all this together, you have a very interesting picture.”

Most of Hasan’s work doesn’t include images of people but his latest project does. He photographs strangers taking selfies. Using the metadata from his images, he scours the Internet looking for similar metadata and finds other images. From these, he is able to identify the selfie-taking individuals down to their name, often via their social media profiles. He acknowledged that this project challenges consent and the idea of public space.

“When you upload that image to Instagram, you’re licensing that image to them. Why are they allowed to do whatever they want with it but not me as a user? We’ve had over a 100 years of understanding what is expected privacy inside someone’s house vs. what is if you’re walking down the street — where my camera is the least of your problems; there are hundreds of cameras all over.”

Image from Hasan Elahi

“For us to pretend the camera is a 19th century tool is flawed. What does photography mean right now? I look at the selfie as a very political act… Today we have this global war on terror and the selfie is its cultural product — when we take that photo it’s a timestamp of I’m safe, I’m okay, I’m reporting it. This repeated loop of continuously surveilling ourselves becomes that timestamp. It’s the action of the photograph, not its product.”

“And when we take a selfie, we hold out our arm in front of us, or we take them in the mirror, if you follow the trajectory of your line of sight, that’s almost always where the surveillance camera would be mounted. Our mobile phones become surrogates for these surveillance cameras watching from above.”

On surveillance and watching

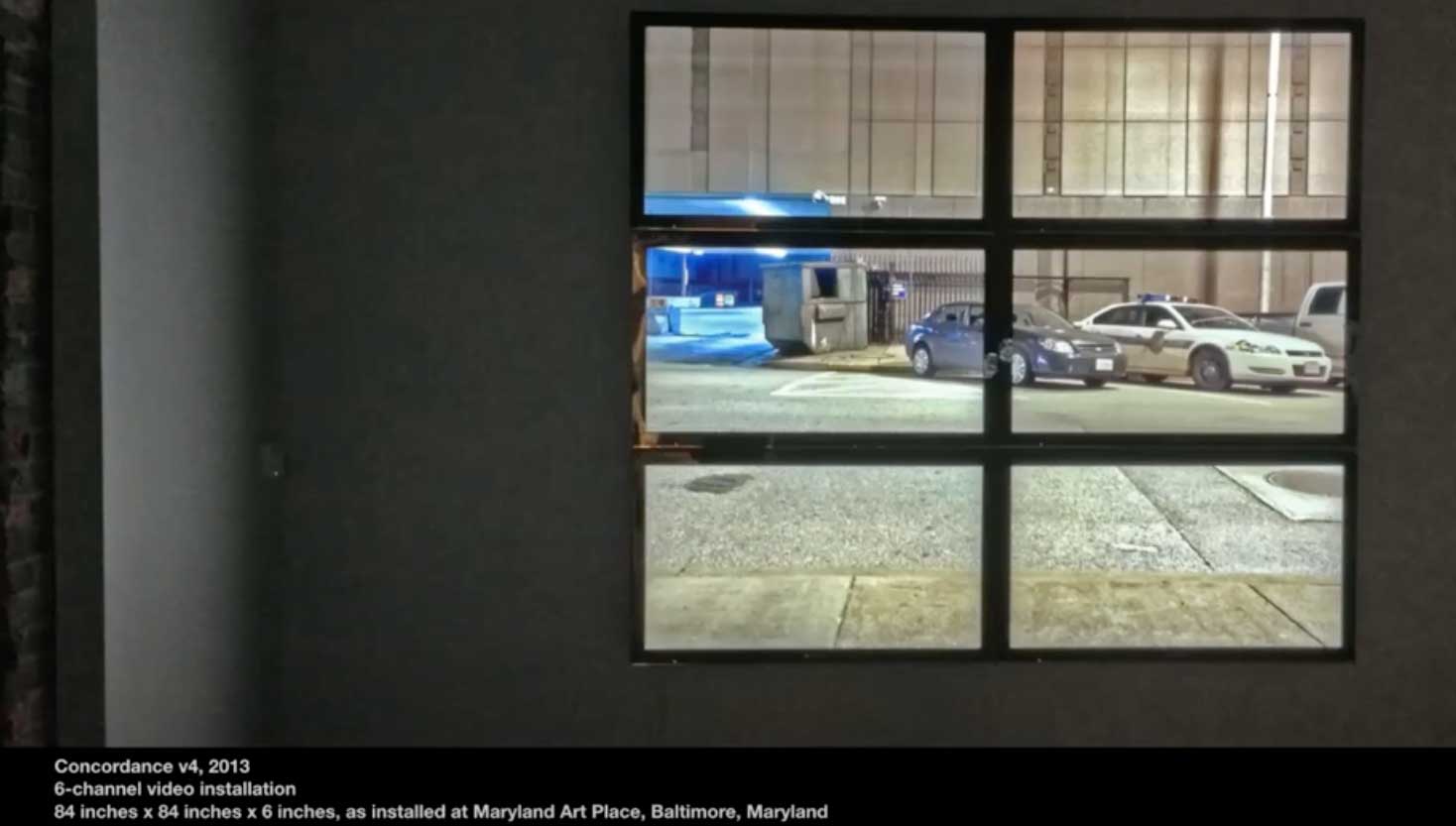

Hasan finds the idea of watching interesting. Concordance v3 (2013) was exhibited in a gallery space directly across the street from the Baltimore Police Department. It resembles a window but actually shows exactly what was on the other side of the wall, like what a surveillance camera would see.

It’s me watching them watching me watching them, back and forth, a little cyclical loop and holding up this mirror to their surveillance device.”

In Concordance v5 (2014) and Concordance v6 (2014), Hasan explored “what happens when the form of surveillance is fractured — your brain again completely rejects it as surveillance”. Orb v2.1 (2014), a 72-channel video installation comprising about 70,000 images, “looks like landmines, but could also be satellites that call and respond, transmit”. Thousand Little Brothers (2014) is a massive work of 28 feet x 16 feet that “at first looks like a very modernist colour field painting… is like a 21st century version but fraught with suspicion.”

On Singapore and on Shroud

Hasan was excited to present his site-specific installation, Shroud, in Singapore, specifically at a historic building: “When you look at Singaporean architecture particularly on a global scale you don’t think of buildings from the 1800s like Objectifs, more like glass-and-steel towers like Marina Bay Sands. Instead of being invisibilised, older buildings in Singapore are literally being demolished.

Installation of Shroud at Objectifs, 2020

“Singapore has also been at the forefront of surveillance way earlier than other countries but has always kept a low profile. The idea of blending, camouflage, hiding in plain sight is very common there… Singapore is a tiny speck geographically on a global map but has massive military might and intelligence.”

“With Covid-19, we’ve been giving up our personal data for health and safety tracking but on the other hand Singapore has done this with national security for a long time. Perhaps because culturally this level of surveillance has been so embedded all along, not even knowing you’ve been watched, Singapore was effective at battling the coronavirus.”

In the green ‘windows’ of Shroud, Hasan has also added the local army uniform camouflage patterns. “Singapore is also one of the few countries with mandatory conscription. When we talked about camouflage, it’s like almost every man in Singapore has worn that uniform and knows exactly what that pattern is.”

When Hasan was in art school, he was put off to learn that the artist Dan Flavin, whose works he loved, “didn’t even touch his works during installation but would just point and the electricians put the whole thing together. I thought, what kind of an artist doesn’t even touch their own artwork?” Hasan was reminded of this again when he realised “I had not only never touched some of my works; I’d never seen them with my eyes, offline. I design my works, send them to [the presenting organisation], who sends it to a printer, then it’s installed and I’m sent photos of it. I found it repulsive 25 years ago and I’m totally embedded in the system myself today!”

“Now I get images of people taking photographs of themselves in front of my works and I have no idea who they are. But when I see a human in front of it I get a sense of its scale. Social media has further expanded the work. Every few days an image from Objectifs would pop up with the [Gallery’s] yellow background. There’s something beautiful in the way that people have embedded themselves and their photograph becomes yet another work.”

On his work in the context of the 21st century

Hasan has been working on Tracking Transience for over a third of his life now. “It’s very much a snapshot of, an artefact of and in resistance to a very specific post 9/11 political, cultural and technological era in the United States. Giving so much information that you would become anonymous was a tactic that only worked in an analog system. Machine learning was in its infancy then. We’re a fifth of the way through the 21st century now! Disengaging from technology was never an option but especially isn’t now; if you’re off the grid, you simply don’t exist.”

2-channel video installation of Tracking Transience at Objectifs, 2020

Younger students he shows Tracking Transience to “don’t get it, because it looks like their Instagram feed, and you realise how much normalisation there has become of self-surveillance.

There was a time we feared Big Brother but now we are our own informants. We watch ourselves and voluntarily share. What is public and what is private space?

We tend to think of what is out there and what is personal. But a democratically elected government is actually public — owned by the people — and the private is how we treat Facebook or Instagram. The corporatisation or privatisation of public data gets really blurry.”

“Democratically elected governments are accountable to citizens at some level. In theory there is a mechanism, voting, that allows the public to be involved in government decisions. Google and Facebook do not have to tell you what they’re doing with your data; they only have to answer to their shareholders.”

“It’s really problematic when so much power and information is limited in so few hands and there is zero incentive to change that structure. When you hit ‘I agree’ on end-user license agreements, the reason they’re 70 pages long is that it’s set up to benefit and protect them, not you. We are so repulsed by the idea of governments taking our information but are so willing to give it away to corporations. We’d be disturbed if a government agent witnessed this conversation but are ready to share it on Zoom.”

Please stay tuned for the next edition of Stories That Matter 2021!