A talk by Dr Patrick Wade

Stories That Matter is an annual documentary programme by Objectifs that looks at critical issues and the possibilities of non-fiction visual storytelling. The theme for 2021 was Mediation/Circulation, which looked at the mediation and circulation of documentary images, in turn posing questions about how they impact our understanding of visual culture as audiences, creators and publishers. As part of the programme, Objectifs presented three public talks with artists, filmmakers, NGO workers and academics.

In From icons to memes: The afterlife of an image, Dr Walter Patrick Wade, an Assistant Professor of Communication at Georgia State University whose research aims to understand the role of imagery in civic persuasion during moments of public controversy, provided a survey of iconic and virtual images and tracked how they have become part of our visual repertoire. His presentation considered the afterlife of the image beyond its original context, focusing not just on what image makers accomplish with pictures but also how audiences adapt them for their own purposes.

Circulation and the meaning of the image

Dr Wade began the talk by asking, “Where does the meaning of the image reside, and who decides its meaning? This is extremely important for thinking about what’s at stake and the shift from mass media to digital media, and the shift from the iconic image to the viral image or the meme.”

According to Dr Wade, circulation is a key word to keep in mind. “We can’t understand images of war or any other images — from advertising, charitable images, documentary, news images — without understanding the channels through which they move.” His talk sought to convey to the audience “how images travel, how they circulate, and how focusing on circulation changes our theories of photographic or visual meaning”.

“Images are not just endowed with a single meaning at the moment of their creation. The meaning of the image is created at a variety of different moments of perception. Context is important; we need a broader account of the entire environment in which meaning is made in order to understand what we’re doing.”

Theories of photographic meaning

How do we begin to make sense of an image? Dr Wade started by looking at different theories of photographic meaning.

- Creator-based theories of the meaning of an image see the meaning as determined by the creator at the moment they select, edit and post an image.

The photographer’s intent, their design sensibilities, their artist statements, the introductions to their coffee table books, and more are all paratexts guiding the way we look at the work itself and give us a sense of its meaning.

However, creator-based theories ultimately narrow our view of photographic meaning because it discounts the audience’s interpretation of the image independent from the will of the artist. In addition to never being able to fully know the photographer’s intent, photographs can capture much more than the creator’s intent even in highly controlled situations.

- Formal or semiotic theories of the meaning of an image suggest that meaning is created through the interplay of visual elements within an image. Different aspects of the image will convey certain symbols that are conventionally coded in our culture to have a certain meaning, and audiences are able to pick up on these meanings and reconstruct the image.

The problem with formal or sciatic theories is they have a tendency to assume that the image doesn’t have more than one possible interpretation. We lose out on the possibility that we might be surprised by what’s in the image, that image might have multiple meanings, or that the creator might intend something different than the audience infers.

- Reception based theories of meaning

Dr Ward referenced Stuart Hall’s famous essay ‘Encoding Decoding’, where meaning is encoded at the moment of creation by a creator, but what the audience takes away, or does with that meaning can be very different from the meanings in the image or the intent behind the image. He cited an example of fanzines that are collages of other texts, such that the adaptation and reuse of the material creates something entirely new.

These visual materials become part of a larger visual repertoire, where anyone can become a producer of images. Image creation is no longer gated behind professional expertise or mass media channels, and this process has become accelerated by digital technologies.

However, an issue with relying solely on reception-based theories to understand the meaning of an image is that many possible readings emerge.

Therefore, it is often a combination of creator’s intent, the formalism of the image and the audiences’ reading of the image that allow for a deeper understanding.

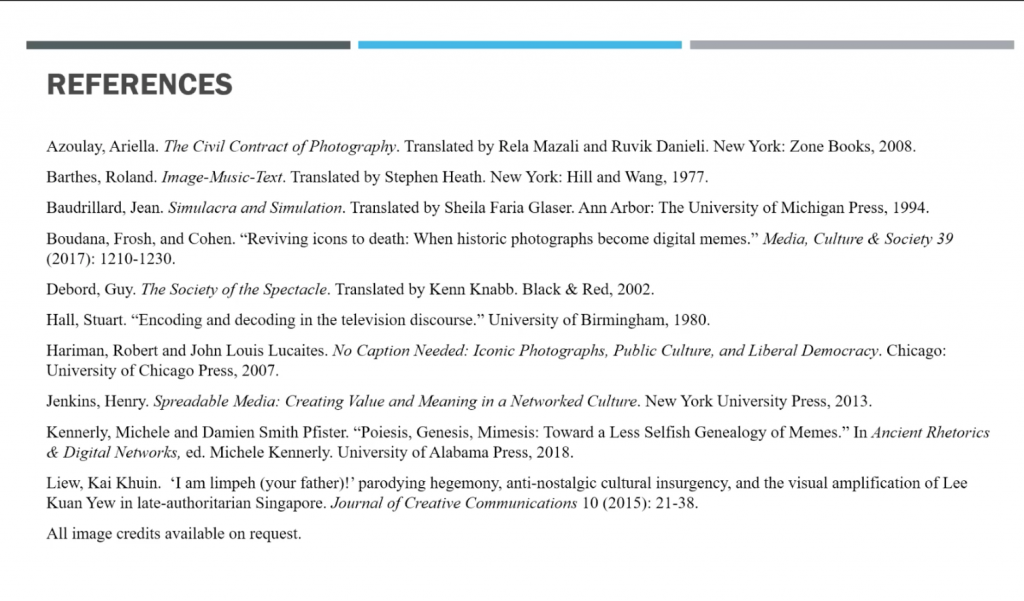

Dr Wade citied the work of Ariella Azoulay, Robert Heriman and John Lucaites that describe the coming together of these different moments as an encounter between the image and the spectator.

“When we say that it’s just the image, or it’s just the photographer, or it’s just the moment of reception, what we’re really doing is we’re freezing the image in time, and that its meaning is exhausted at this point in time. When we start reading it as an encounter, we start tracking the image as it moves from one context to another, and in its circulation, how it generates new and novel meanings with each encounter. This opens up our understanding of the image and what the image can do.”

The iconic photograph and its afterlife

Dr Wade citied a quote from Robert Heriman and John Lucaites’s seminal text on iconic images:

“Those photographic images appearing in print, electronic or digital media that are widely recognised and remembered are understood to be representations of historically significant events, activate strong emotional identification and response and are produced across a range of media genre or topics.”

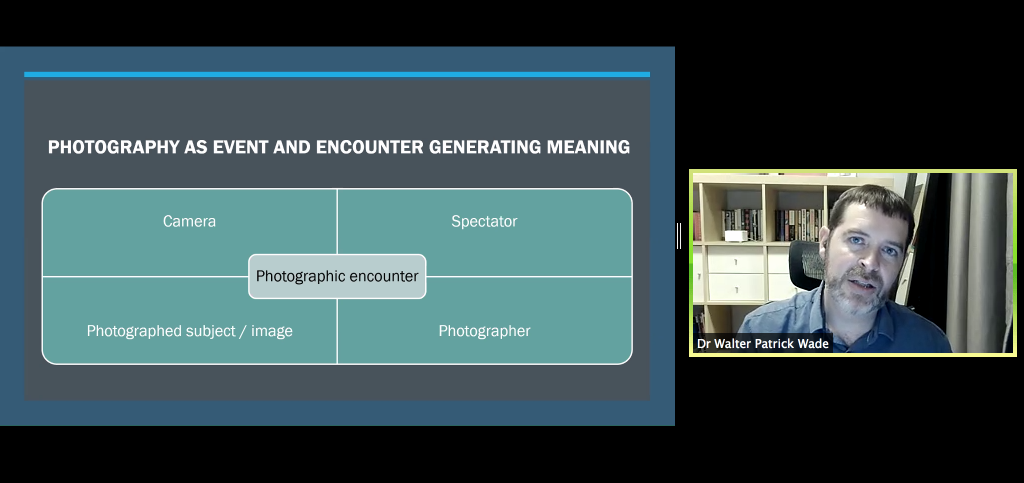

While there are no objective standards for an iconic image because the criteria is deeply entrenched in cultural values and can change with the passing of time, Heriman and Lucaites identified 5 characteristics of an iconic image:

What is interesting about iconic images is that they are so significant and well remembered that they become part of a visual repertoire and a resource that is used in a variety of contexts. The formal character of the image persists as a reference point for other cultural producers to riff off, remix, parody and to use pastiche. These new iterations of the image frequently carry a reference to the values contained within the original image.

Dr Wade put things in to a local context with the iconic image of Lee Kwan Yew crying when announcing Singapore’s separation from Malaysia. Referring to Heriman and Lucaites’s criteria, Dr Wade pointed out that the image is aesthetically familiar in how it features a highly recognisable figure in an important moment in Singapore history, and is an image that is circulated and re-circulated in media publications and national events. “It coordinates a set of values about stoicism and the display of affect; here we have kind of manly restraint, but also a deep well of feeling for the nation and anxiety about the future of the nation, and a civic performance of leadership in a time of crisis. Those things together channel feelings of the public, while managing the crisis of separation.”

He then looked at how the image circulates. For example, at an exhibition at the National Museum of Singapore, it was voted the most powerful and most touching out of several 100 photographs. When other politicians including Lee Hsien Loong or Lawrence Wong cry, the screencaps from live television follows the visual form of the earlier image. This is an image that has an afterlife beyond the context of the 1960s and the separation, and has a lasting impact that resonates in the current day.

By using the theory of visual iconicity, the iconic photograph is not just about reading the image formally or thinking about the creator of the image or its reception; thinking of it as a repeated encounter in time allows for adaptation, and an understating of how the image works.

Transiting from an iconic image to a viral image or a meme

In current era, all of us are producers of images thanks to technology. The result is that we now have more visual resources and a wider visual repertoire than ever before.

Dr Wade spoke about the viral images that circulate widely through digital networks, where “going viral”, means that the image has had extensive reach, has acquired collective familiarity and is subject to proper free circulation within social media.

However, he pointed out the need to be cautious about the language of virality, which biologises the human communication processes. Describing visual communication as a virus doesn’t actually explain human communication and interaction, which are much more of a back and forth, and much more complicated. Often times, a viral message implies a kind of secret of transmission that ends up getting manipulated by businesses or social entrepreneurs or others as a secret source of power.

“Rather, people are spreading the image because there is something compelling about it that they find worthy of recirculating, sharing or adapting. We need to insist on the role of human agency in choosing to appropriate, adapt or recirculate visual memes.”

He points out the differences between iconic images and viral images, summed up in the presentation slide below:

Dr Wade surmised that when the iconic transitions into the digital format, it actually starts looking more like a viral image. Viral images are obviously circulated extensively through digital media channels, often with the aim to shock, entertain, or impress their audience rather than with the goal of responding to some recurrent crisis facing the Republic. While it can be a mode of civic performance, it’s also a variety of other kinds of communicative action.

Within the context of Singapore, Dr Wade citied an image of Lee Kuan Yew that is now used for any kind of caption that the speaker wants to attribute to the late Mr. Lee. These sorts of images have been analysed by Liew Kai Khuin (refer to references).

“The image has become a meme template that gets used and then circulates in a way that allows the person adapting it to comment on different things happening in Singaporean society or culture, independently of the wishes or desires of Mr. Lee. We see how this is going to allow for more indecorous, but also more open and less bounded engagement by the users who are adapting these messages.”

Dr Wade stated that the shift from the iconic to the viral within the theory of visual meaning, is a shift that is emphasising the spectator as creator and the role of the spectator in the encounter. These are becoming more important than other aspects of meaning making highlighted earlier in the talk. It is about the creativity, the generativity, the idea that these images are resources for new acts of communication.

If that is the way that audiences understand the images being made today, artists, graphic designers and users of social media need to ask themselves:

What are people going to do with the images that I’m producing? How am I contributing to the visual repertoire of a citizenry that is increasingly talking in pictures?

Audience question: It seems that viral images are unrooted from a kind of ethical or moral kind of grounding. So what does that mean?

Dr Wade: If we think about iconic photographs that have an implicit moral content or moral judgement, when the image gets riffed on or parodied, it’s there in the background, criticising the behaviour that isn’t following that model or that standard.

But when it becomes unrooted from that context, it can now be used to make any number of wildly different moral claims. Now, some memes just want to shock and be offensive, although you could read that as a kind of cynical moral posture, but some of them do intend to make moral kinds of claims. I think the best example of this is that Lee Kuan Yew template that gets used by Singaporean cultural producers, whether we’re talking about sgag, we’re talking about someone’s Instagram feed or Facebook post. There’s there’s no longer the moral core of Lee Kuan Yew, his values and ideas, right in the background, criticising whatever’s being said.

In fact, there’s a kind of new moral centre in the statements that are being made by the person who’s posting the image. While there’s definitely a moral argument to be made against that practice, but it is happening.

How might people, visual artists, photographers, lean into the kind of creative possibilities of viral imagery?

Dr Wade: We all have images that we can refer to and use at the push of a button, the easiest example of which is an emoji keyboard and gif libraries. We have these visual repertoires that we know how to tap into, and that are used to communicate the same way that we communicate with words. On the other hand, we have older ideas of image production as something that is the domain of the artist who trains for years to produce a particular kind of image with a particular kind of goal.

While that is still valuable, the fact is that image making and sharing is something anyone can do. When we think about image sharing that way, it changes the way we think about what we produce. We are then not just thinking about producing something that’s going to impact the world. We can think about making something that’s added into the visual repertoire of other people to share.

I don’t think it changes the nature of the work or the process, and I don’t think that all artists should be doing things this way. It’s just an additional thing to consider when you’re doing your work.

As someone who works with photography, I sometimes don’t see the value of making one more image of the same thing, especially when I hear you talk about viral images, it makes me say no, almost.

Dr Wade: If there’s space for optimism on this question, it’s that every encounter between a spectator and a photograph is a unique one. Even when you’re circulating something that to you is a cliche, it may not be a cliche to the person that’s looking at it.

When we think about things like news coverage that way, I think enables us to say, well, this is what I have to say to these people at this point in time, and someone else said it to different people in a different point in time. Also, when we talk about the kind of work that artists produce, there is a demand for novelty and being in a dialogue with the community.

In relation to broader publics, I think there’s a lot more space for the mundane, the average, the cliche and the every day, to continue to have an impact and have value, because we’re talking about a bigger and more dispersed audience.

If there’s one shift that’s happening in visual studies in the last five or 10 years that I think is very important, is that there’s been a move away from postmodern critiques, ideology based critiques that the image is somehow dangerous or unsavoury or problematic, in favour of a set of approaches that while recognising the dangers of the image, also acknowledges that images are a lot like words.

Images can lie to us, trick to us and mislead us, but they’re also the building blocks of our community.

So there’s a lot of work going on in visual studies, in communications and related fields, that’s trying to figure out how those spaces for encounter, how those communities are being formed through images.

Here are some resources that Dr Wade made reference to in the course of his talk: