Filmmaker Tan Wei Keong and writer Alfian Sa’at in conversation

Our second Objectifs Film Club session, held online in May 2020, featured filmmaker Tan Wei Keong and writer Alfian Sa’at in conversation about The Great Escape (2015), Wei Keong’s short film inspired by Alfian’s poem of the same title (rent the film and read the poem here).

Read on for a recap of their conversation.

The conversation has been slightly paraphrased for brevity.

Wei Keong: The Great Escape is a short film I adapted from Alfian’s poem of the same title. It was commissioned in 2015 by Utter which is part of the Singapore Writers Festival and supported by the National Arts Council. One of the reasons I chose to adapt Alfian’s short poem is because it offers a lot of space and room to think about what I can translate the words into as visuals, as opposed to a story which has more plot points and people. For me [the poem] is more open ended.

Alfian: I wrote this poem a long time ago, when I was maybe 20 years old. I realised belatedly that it was actually inspired by a film. When writing it, this was a bit subconscious but now when I revisit it I realise I must have been influenced by one of the scenes in Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together. In that film two lovers played by Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung make a promise to visit a certain lighthouse at the end of the world. This is an actual lighthouse somewhere off the southern coast of Argentina. But at the end of the film only one lover makes it. Something in that made its way into my subconscious and was breathing down my back as I was writing the poem.

Alfian: So I feel like the lighthouse is reincarnated as the hermit’s cottage in my poem. This is an interesting kind of pendulum, a film to my poem and then later to your film, Wei Keong.

Wei Keong: What were you thinking, what was on your mind when you wrote this poem? Are there any visuals, or which line is your genesis? Is there a first line of conception?

Alfian: I started out with this idea of two lovers eloping. The sense of elopement is also something that is so pregnant with promise, that they’re going to have amazing adventures ahead and they’re going to have them together. They have no idea at that point of time that somewhere ahead the road will bifurcate and they will be going on different journeys. In the beginning there was all this sense of adventure and promise.

The one word that probably was the seed of this poem — or maybe not the word but the line — was “We will wake at dawn”. All that preparation where you’ve packed, getting ready, even the night before maybe you couldn’t sleep too well, you wake at dawn and then you’re off on this amazing adventure with this person who you think might be your lover for the rest of your life, but of course life doesn’t work that way — in the world of the poem, at least.

Wei Keong: When I read this poem I was hit by a lot of the phrases that resonate a lot with my personal life, especially the line “I wind down the windows and a breeze / steals in to unfasten our smiles.” and also “fresh gossip from the wind”. It just brings me back to myself and my husband in the car when we are travelling to this house that was depicted in my short film, which is interestingly also at the end of the road. So it kind of matches, parallels a lot of things I have in mind and hits a lot of home runs for me. That’s why I thought I need to do something with this.

Alfian: All these confluences… Could you tell us a little about this house? I want to have a kind of picture. Where is it — countryside, urban?

Wei Keong: The house is very [much in the] countryside. It is 2.5 hours south of Mount Fuji in Japan. I was working as an animator in Tokyo when I met my husband. It is very isolated, away from the bustle and noise from the city. There, I felt like this is our world, I felt very protected, it’s very internal and away from all the things that affect what should be about the two persons.

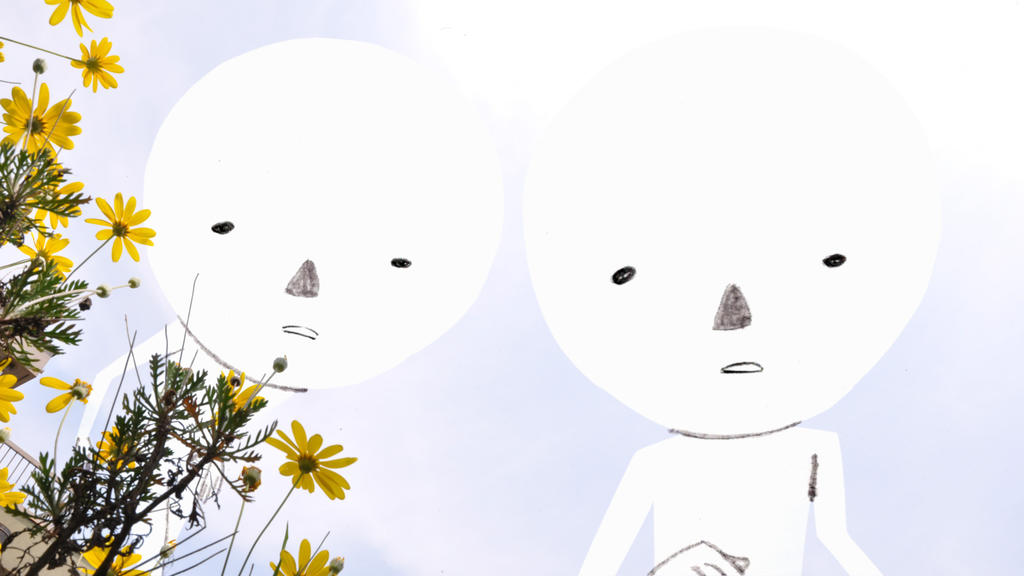

From “The Great Escape” by Tan Wei Keong

Alfian: A few of my texts have been adapted into short films: my play Katong Fugue which Boo Junfeng turned into a short film [rent it here on the Objectifs Film Library] and some stories from my short story collection Corridor which the filmmaker Abdul Nizam made into a TV series for Suria. But this is the first time someone has adapted a poem of mine and I remember thinking that actually the perfect form for a poem would be animation.

Wei Keong: Why did you think that?

Alfian: I don’t know whether I’m stereotyping, I just feel a kind of abstraction in animation and this wider horizon of possibilities that lends itself better to a poem. Maybe I’m simplifying things, you know, but I really do feel you can do so many things in animation. Unless you’re an experimental filmmaker, if you’re filming something you’re sort of tied down to the real.

Wei Keong: I think it’s also because a poem is capturing a certain moment of emotion — I may be generalising as well — it’s trying to describe an emotion, a slice of time in very few words and maybe that’s why you’re thinking in the direction of experimental animation or things that can only be depicted graphically.

How did you feel about filmmakers wanting to adapt your texts? How’s your relationship with the filmmakers? Are you protective of your texts or more “do whatever you want”?

Alfian: I always feel like a play and a film are more similar as opposed to a poem and a film or even a short story or a film. There are more levels of adaptation. I found myself very humbled by filmmakers who look at my playscript and tell me, this page don’t need, because I can do it with two visuals. There’s a part of me which feels like oh my god, what, I wrote all that text for nothing? but I recognise that the grammar of a film and the grammar for plays are very different and sometimes when people adapt plays for film but don’t cut out a lot of the fat you end up with a very talky, very “stagey” film.

There are wonderful talky films I love by Eric Rohmer and Richard Linklater but I do feel that with film there’s really the art of compression and for me it’s primarily a visual medium. I’ve heard filmmakers who come to watch my plays say Actually I find watching plays very boring because there are no cuts, no scene changes or they’re few and far between. Then there’s also just a wide shot, you don’t have different shot sizes, close-ups. That kind of palette, syntax is not available when you’re making theatre. I think I realised they are different forms and therefore I’m not really possessive how the adaptation works out.

Wei Keong: I’m also watching more plays now that theatre groups internationally and locally are uploading their plays online. I realise it hugely has to do with the content of the plays. For example I watched MERDEKA [written by Sa’at and Neo Hai Bin]. I don’t see it being on film because there’s so much information. I really enjoyed it. I can see there’s content for this kind of form which would be difficult to express in other forms as well.

Alfian: I am really in two minds about digitalisation of theatre.

Wei Keong: Do you want to talk about it?

Alfian: With Covid, there’s a part of me that’s slightly envious of filmmakers because if they want to share their work during this period it is the work. Of course you can argue about whether it’s better viewed on the big screen, but I always feel like the recording of the play is always a compromised product. It cannot substitute the real thing.

Recently T Sasitharan from the Intercultural Theatre Institute wrote this really lovely essay in The Straits Times where he talks about the importance of live theatre and he says that recordings of theatre are “porn”. It’s a simulation of the real, can never approach the authenticity of the real thing. I won’t go as far as that but I do admit that what we have are mostly archival recordings, so they’re not created with the same kind of intention and artistic integrity as a filmmaker and his film.

Wei Keong: I’m very conscious, hyper aware when I’m watching a play like that that this is not the way it should be watched but for now it is okay. Especially for plays that couldn’t have been staged in Singapore or plays that have happened a long time ago.

Alfian: It’s so difficult to tour a play. That’s something I’ve also been envious of filmmakers for: their mobility. For a play to tour I have to ask if all the actors are free and try to match everyone’s schedule and bring the whole production over, the carbon emissions when you fly… with a film you can just send it over WeTransfer and get a screening somewhere else!

I want to talk more about The Great Escape. In the film there seems to be a kind of blended animation. Is that the term for it?

Wei Keong: Mixed media?

Alfian: Could you share a bit about why you chose that kind of design for the work?

From “The Great Escape” by Tan Wei Keong

Wei Keong: I more or less use the same techniques in a lot of my other short films. I studied animation at NTU and come from a traditional animation background but we are also taught the 3D animation pipeline, which as a lot of people know is a huge process. You can’t really do everything by yourself. So since I graduated from school I’ve always thought of ways to be able to make it feasible to complete an animated short film with a very small team. I think that’s one of the challenges.

I think a lot about it and it shouldn’t be because it’s easier or cheaper but also that it needs to fit the content — what kind of story you’re talking about and why it is important to use photographs, time lapse, photographic depictions in my short film. A lot of my short films are very autobiographical or some parts of it are with reference to what has happened in my life that I want to bring into the short film. Hence the choice to use real photographs or if not real photographs, they’re photos that are printed and I’ve added to it — dots and those very tactile textures in the background, I really like it.

Alfian: Do you feel that kind of reference to actual images or photographs is a way for you to “signal” that there are autobiographical elements in the work?

Wei Keong: To a certain extent it’s to hint that way. Everything is drawn or stylised, there’s more fantasy, it’s more dreamy, that’s the good point. But it also loses a bit of reality or it doesn’t tie back to the world we come from.

Alfian: I’ve always had this question for animators in general. What are your thoughts on what I think is a tendency for Hollywood animation towards CGI, trying to recreate the real? The laws of physics are like this and therefore the hair is going to fall this way…whereas for me part of the joy of watching cartoons was seeing Wile E Coyote defy physics, rather than to conform.

Wei Keong: It’s also about trends. Computer graphics that have been made popular by games like Final Fantasy generate and render hyperrealistic flawless skin, flawless hair flowing. It kind of entertains a bit of fantasy and perfection to a certain sense but both mediums like traditional hand drawn animation vs CGI computer graphics have their good points.

I totally see why certain stories use certain styles but I want to point out that a lot of Asian productions tend to look towards or copy western influence and I think that is a no-no. You lose a bit of the culture if we always look towards Pixar or Disney or even if we do traditional 2D animation and we look towards Miyazaki from Japan. There’s always a feeling of catching up. I’m always encouraging people to just find your voice in terms of what style you want to use.

Alfian: Recently I revisited the animated film called Havoc in Heaven, from Shanghai Animation Film Studios in the 1960s and I was really struck that they weren’t trying to do something Disney-fied. The fluidity of the lines, the linework seem to borrow from Chinese painting and motifs. The way they rendered the clouds even, you can recognise it immediately, that it comes from a particular visual culture.

Wei Keong: I was so glad to catch your talkback for Monkey Goes West. You mentioned Havoc in Heaven and it struck me because I’ve watched it as well but I didn’t remember it until you mentioned it in your presentation. I connected very quickly because that image of how the Monkey King looks and the style of the clouds imprinted on our impressions very long time ago.

Alfian: The sheer choreography of the fight scene too, I found that really amazing. It’s like someone swirling brushstrokes in the air, it had that kind of fluidity.

Wei Keong: You do a lot of research before you write. What kind of research do you do before you do something, or what is your process like?

Alfian: For a lot of my sociopolitical works, I definitely love rummaging through the archives. The poet Adrienne Rich says if you’re going to write about women braiding each others’ hair, you should know what kind of braid it is, whether they’re using seashells, and then she says, you also have to know what else is happening in that country. Just a kind of technical knowledge is not enough, for me you really need to have a much wider sociopolitical knowledge about something.

That said though, in this particular poem The Great Escape I was writing in a much more confessional vein, the lyric poem I don’t usually do because I feel I’m quite a private person. I wrote the collection The Invisible Manuscript which is a collection of queer poetry when I was maybe 20 years old and I did not publish it until very recently, I think 2014 or so, when I was in my late 30s. A lot of it comes from me struggling with this idea of disclosure and some form of coming out. As a writer, I’ve never been comfortable in a mode where I write about myself and my experiences. I feel that I can be a bit exhibitionist, narcissistic also, so I’m not slamming other confessional poets. I’ve always thought I’m a kind of poet who bears witness, tries to record a political document of his times rather than to write about me and the I. I guess I bent the personal rule a little bit for The Great Escape and you have further amplified that by turning it into a film!

Wei Keong: You don’t want to be baring yourself too much in your words, but then again the text does come from your mind. Something that’s in your brain comes out and you try to disconnect the association with it by taking a very third person point of view. I find that process interesting because when I write my short films I try to be as personal as possible because we always talk about connecting with the audience and if I don’t believe in the story how can I be expected? It’s two different approaches.

Alfian: I think it depends also on the kind of work you’re creating. For me the lyric poem will give it that space for this particular expression of self, self-disclosure. But if it’s more narrative, more observational you don’t have to go there, you don’t have to be so introspective I guess and mine the self for the creative work.

Wei Keong: So when I read The Great Escape, I feel a bit of the sadness and that is one of the reasons why I decided to make the short film, like the continuation of where your text leaves off. The way I see this adaptation is two different stories that kind of foresee what’s going to happen in the future. For me, I took a lighter tone — we do get together, things will get better, I foresee this possibility in the future, and that’s what I usually present in my films. We have seen so many scenes of LGBT relations in bad or sad endings, and I want to twist that kind of direction around and present very mundane day to day things in my films: weeding in the garden, cooking. Nothing is happening, the dialogue doesn’t mean anything, just what normal couples do.

Alfian: I think that’s great because you’ve come up with an alternative conclusion or maybe a kind of sequel, pluriverse where this couple might actually have a so called “happy ending”. Of course that’s a wonderful thing and ties in with all these campaigns like “It gets better”, which is an important message to put out. When I wrote that poem and a lot of other poems in The Invisible Manuscript I was 19 going on 20, a bit angsty, not really too sure where the future would lead me. Nevertheless I wanted to to be pessimistic about it because I thought that is how you should show how adult you are. At that age, if you seem optimistic you [feel you] may not be taken seriously. So at that age you had to write about dark, angsty things to feel like you had some cred.

Wei Keong: Where were you when you wrote this poem?

Alfian: Physically, mentally, or…?

Wei Keong: Both. Do you want to talk about it?

Alfian: Maybe in the army. I think there’s a poem in the manuscript called Making Love in Army Bunk Beds is Wrong. I can sort of locate the time to around there but it is quite a sad book I feel and once it landed in your lap… you’re someone older than 19 who’s had a bit more life experience, who has reached that horizon of possibility that as a gay person you can get married. I felt there was something very restorative about your film. In a way, an older queer person telling a younger queer person it doesn’t have to end his way. It gets better.

Wei Keong: I think your text really gives a lot of hope to a lot of people as well. We have a lack of representation in Singapore in terms of LGBT themes, even just writing the presence of LGBT relationships or even just talking about us as ideas is strong enough for me.

Alfian: I wanted to share something I read. It’s by EM Forster. He wrote a novel called Maurice for which he said it was important there was a happy ending: A happy ending was imperative.I shouldn’t have bothered to write otherwise. I was determined that in fiction anyway two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows.

Obviously Forster was writing in a very different period when homosexuality was still criminalised. So fiction allowed him that space to create happy endings. What I think is interesting is that we’ve moved on from that. In your film, the happy ending is reflective of what is actually possible during this moment in history.

Wei Keong: I wouldn’t say it’s a happy ending — happier than your poem perhaps — but I’m just opening up possibility that this can happen, don’t say never. Actually in The Great Escape I didn’t really say it’s two males or two females, it’s just two non-gendered characters, we don’t even have dialogue in the films. But people who know what I do in my films will kind of get it straight away, so it streamlines the open-endedness of the poem.

Alfian: Could it also be one male and one female?

Wei Keong: Yes, I think so.

Alfian: I think this is actually a good time to open up to questions from the audience. Here is the first one: If you had a choice to adapt any other literary works, what would they be?

Wei Keong: I would probably do short stories or another poem because I wanted the room to fill in the spaces. I don’t really like to adapt one-to-one, I don’t think that’s the way to go in terms of adaptations, but of course there are other works that do adaptations very true to the material and that’s totally fine. One of the examples I read recently The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson and they adapted it into a TV series which is totally not the same as the source material. I loved both the book and the TV series and I love how Shirley Jackson writes so much that I continue to chase her other works.

Alfian: The Lottery, wasn’t that by Shirley Jackson?

Wei Keong: Yeah! The way her brain works is very bizarre but it’s so intriguing and it captures my attention from the beginning.

Alfian: I think Shirley Jackson is a goddess…but are there maybe also other Singaporean authors you’ve come across?

Wei Keong: Sonny Liew’s graphic novels. He is interesting. And Amanda Lee Koe is interesting too, her works. I don’t want to play favouritism but I think we have a lot of exciting voices. And for you, are there any of your works you would like to see in a film format?

Alfian: This is a good question. My short story collection Corridor, that’s been done I also just kind of wonder what would happen if different filmmakers were to try their hand at the different stories inside. Most of them are in the vein of some kind of social realism. I’d love to see if Kirsten Tan has a treatment; Junfeng, my good friend; K. Rajagopal. But it sounds like such a vanity project — I choose you! I sound like I’m designing my own retrospective.

Wei Keong: Do you feel it’s important to talk to the filmmakers before they run away with your text or do you feel they should be independent in terms of the author and the filmmaker?

Alfian: I always think the best collaborations have to begin from a position of mutual respect. If I am already a fan of that particular filmmaker’s works there’d be complete trust in what this person would do with [my text]. It’s very different if I don’t know the person’s work because sometimes some of the adaptations…not to put down students, but some student adaptations can be quite problematic. For example when they say Oh, in my school it’s very hard to cast a certain race. Can I turn this character from this race to another?

Wei Keong: They’re not thinking deep enough about the implications.

Alfian: Exactly. Sometimes for me it’s like if you want to remove lines and replace them, those things I can take, but if you want to do certain things like changing the character’s gender or race, the dynamics are quite unsettled.

Wei Keong: How would you encourage young writers to create poetry and prose from what inspires them?

Alfian: The encouragement I’d give any writer is to read, read and read.

I always think of the act of writing as an aeroplane taking off but you cannot just take off like that, you need a runway, which you have to construct with all these books that are your predecessors and ancestors. I think as writers it’s crucial to know who wrote before you. You’re never just writing on a blank piece of paper. As a playwright in Singapore, I’m writing over Kuo Pao Kun, Haresh Sharma…so I’m negotiating with a tradition. The best forms of writing I think don’t just emerge out of nowhere. There’s some kind of dialogue with tradition, so read and read. Build that runway before you take off.

Okay, I like this question for Wei Keong: did you have to navigate any censorship with NAC when making this film, because it’s a commissioned film, right?

Wei Keong: I don’t remember any objections from NAC or the Singapore Writers Festival because I had two producers to deal with all these discussions. After telling them what I was going to do they talked to SWF and NAC and usually I don’t really care so much about censorship, I usually speak my mind and whenever it comes back in terms of rating or you shouldn’t do this I will adjust accordingly or decide not to do the project. How about you?

Alfian: Same as you. When it comes to censorship, just don’t self-censor because you’re doing someone else’s job. Why do that when they’re getting paid to do that? I think it’s so important to keep on pushing, it’s the way to keep on testing the censors’ thresholds. The more the censors are exposed to works which seem to “violate their codes”, the more I think the next time there’s a censorship review they can’t help but try to shift it in a more liberal direction.

Wei Keong: Culture is moving, right? It’s fluid, it’s not black and white. Whatever theme you’re talking about is not presented in black or white, it can usually be reflected in different ways. So just play around with the themes and topics and get around red tape.

Alfian: I like what you mentioned about your producers because it’s good to have producers who will walk alongside you, fight for you, aren’t there to police you. Sometimes producers have this bad rep, especially Hollywood producers, for example, that they throw money at you but at the end of the day what’s produced is unrecognisable.

Wei Keong: If you realise that the dynamic between the producer and yourself as a creator doesn’t match at all, it’s time to move on. It’s okay to say no and there’s someone else better out there.

Alfian: Another question from the audience: Please share the process of your animation. How is animation different from mixed media?

Wei Keong: I think it’s easier to think of animation as film because animation is basically storytelling and using visuals to push the story forward. Animation is just a medium in terms of what visuals you decide to use. In terms of mixed media, it’s just different style options that are available: hand-drawn which is like Disney, computer graphics is like Pixar, the hybrid form which is what I’m doing is basically taking digital media and mixing it so that it looks not familiar but somewhat familiar to what you have always been seeing.

Alfian: Would you say in mixed media you might have photography, for example?

Wei Keong: Mixed media basically means you’re not sticking to one medium. So if you mix 2D with computer graphics, you blend the genre so that you don’t know what you’re seeing.

Here’s a question from the audience: How do you write dialogue in your works? Do you imagine yourself in the character, or…?

Alfian: I think so. One of the most difficult things in writing dialogue is finding a character’s voice, trying to ensure your characters are not speaking merely as different versions of you. I will definitely have my own speech patterns expressed in certain things like “You know?”, “Right?”, those kinds of telltale words. One way to avoid ventriloquising through characters is to really let the characters walk around in your head for a while. Let them take shape, so up here becomes a kind of hotel for them to live in, for them to slowly materialise and then once you can envision them the voice follows.

Wei Keong: How do you decide when a character is ready?

Alfian: When I write plays or short stories I would start from a character profile. Sometimes when you write a script and your characters are just called A and B you will come up with very generic lines but when you think very deeply about why your character has a certain name, who gave your character this name, what’s the symbolism of that name, what’s the surname, etc…

Wei Keong: I write dialogue almost the same way as Alfian. I try to let the character develop more in my head. If I can believe that the presence of this character, what he or she does, then I will start to write it down and like Alfian, I’m quite against giving the characters names before I know what the character’s personality is like. So I would use very generic names like Mother, Son, A, B, before giving them more specific names like Ah Huat or…because if the first step of shaping a character is to give it a specific name you are giving it a personality even without knowing what he or she is going to be like, so I would go towards that development.

The Great Escape, along with with other short films by Southeast Asian filmmakers, is available to rent on the Objectifs Film Library. More titles will be able to view at Objectifs’ premises at a later date (contingent on the Covid-19 situation).