A talk by Manit Sriwanichpoom

Curatorial (Case) Studies is a programme by Objectifs that aims to bolster discussions around curating image-based work. As part of the programme in Nov-Dec 2020, a series of public talks addressed ways of looking at and understanding photography and film in Singapore and Southeast Asia, through the eyes of key practitioners, curators and writers.

Manit Sriwanichpoom, eminent photo artist, curator and teacher, spoke about his journey as an artist and curator. His work has been key to elevating the profile of Thai and Southeast Asian photography internationally.

Manit began his talk with an overview of his career. As student at Srinakharinvirot University in Bangkok, Manit encountered the work of Pramuan Burusphat, which inspired him to start experimenting with photography. “The work opened my mind to the possibilities of photography; it may look ordinary now, but those days in the 80s, it was new.” His early work explored his own identity through self-portraiture and photographing objects from his family home, with his first forays into socio-political commentary, inspired by television reports of the Gulf War.

After graduation, Manit became a photojournalist as a way to earn a living while improving his photographic skills. The job saw him travelling around Thailand, covering stories such as the Burmese civil unrest that was occurring near the Thai-Burmese border. While on one such assignment, Manit had a near-death experience with the Khmer Rouge. This, coupled with the nature of the job where he often found himself just waiting for assignments from the papers, led him to reconsider his choice of career. He decided that instead of waiting for stories to happen, he wanted to be an artist, so that he could tell his own stories.

From ‘Eyewitness’ Magazine, 1986, Image credit: Manit Sriwanichpoom

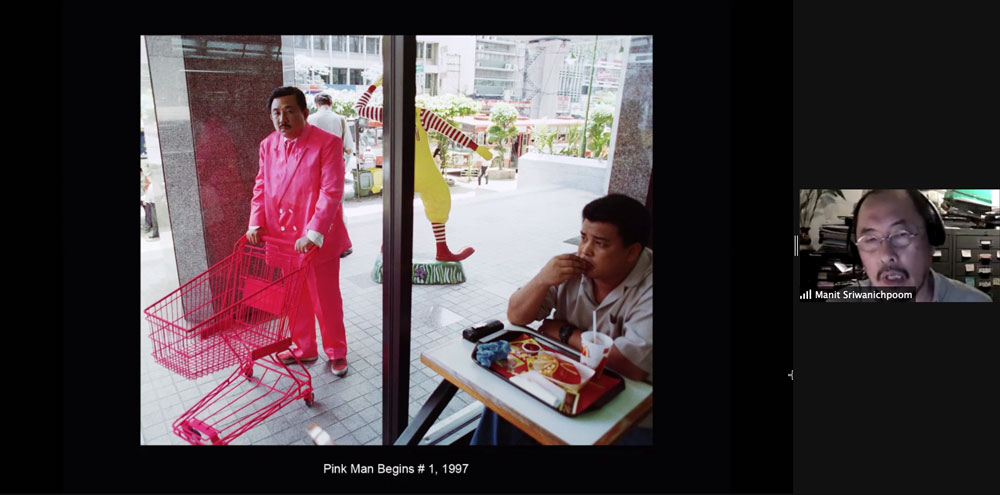

The Pink Man series

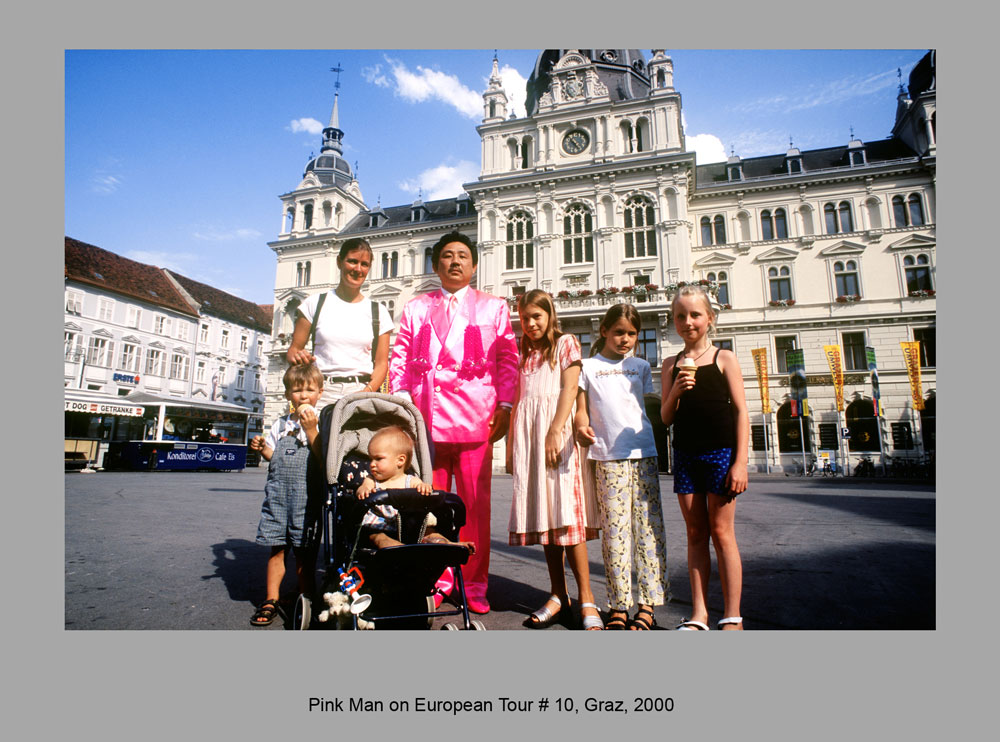

1997 saw the debut of the Pink Man series. While Manit has made many other works, the Pink Man series is his longest running and best-known project to date. The series started as a critique of the wave of consumerism that swept Thailand, just before the 1998 Asian financial crisis devastated the country. As Thailand recovered from the crisis by promoting tourism, Manit’s Pink Man became a tourist, casting a critical eye on how patterns of consumption created an image of a person. Pink Man also travelled into past, appearing in archival photos in a series of images that depicted historical unrest in Thailand. By doing so, Manit’s Pink Man created a dialogue between the past and the present, inviting questions about contemporary politics in relation to Thailand’s history.

The Pink Man series took many forms, from conventional photo prints, to fashion shows and performance art. “I don’t restrict myself,” says Manit.

“ I open myself to everything instead of just using a certain form of expression. If I want to talk about this topic, I ask myself, ‘how can I do it?’ It is about the meaning of the work, and its representation and perception.”

Venturing into the curatorial

Manit’s foray into curatorial work started in 1996, where he organised a one-day art event at Huay Kwang Mega City. He and fellow artist friends exhibited, performed and played music.

“I think art should be open to different disciplines. Even though I focus on photography, I have friends in performance art and music. I have been involved in theatre, in filmmaking. So when I organised this event, we very much enjoyed getting together to do something. Thai people have an artistic heart. They don’t like to follow order 100%. Thai means free man. We are free, so we want to do something.”

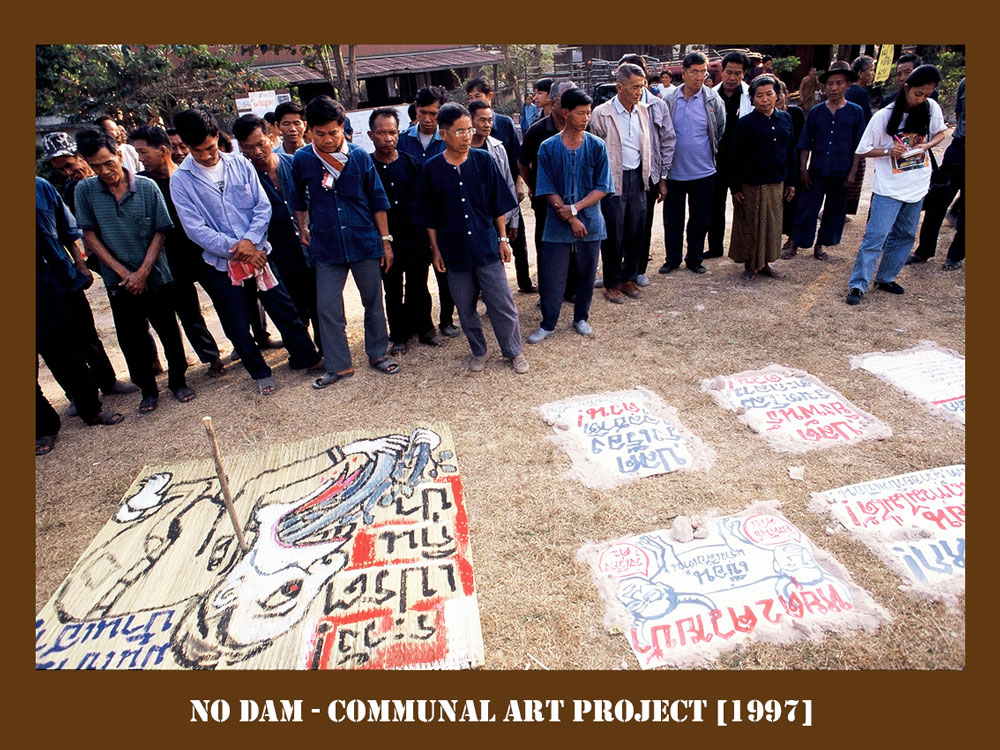

In 1997, he organised a communal art event in a village in Kaeng Suea Ten, located in the Phrae province in Thailand. The artists wanted to support the village’s protest of the building of Kaeng Suea Ten Dam. They created an installation using materials and motifs inspired by the village, and enjoyed music and storytelling with the villagers each night. “I think they don’t know whether to call it art or not, but I also don’t care if people think it is art. It is our way of supporting the villagers’ fight against the government.”

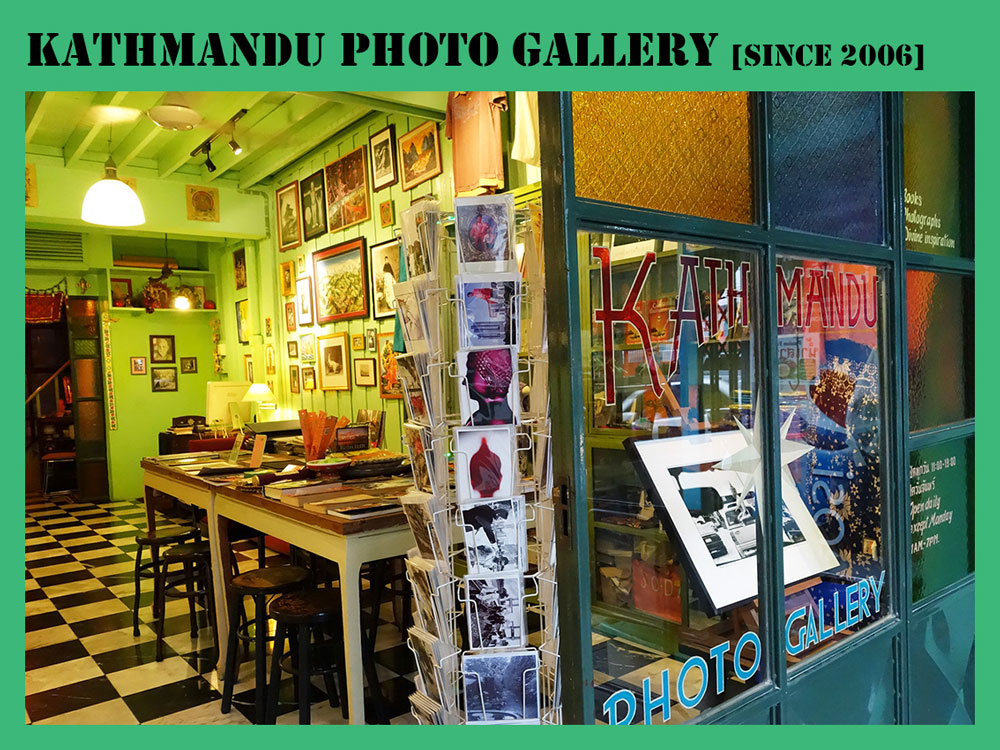

Manit subsequently began organising shows in more formal gallery spaces such as the art centre of Chulalongkorn University. As he became involved in more shows, he took on the mantle of a curator as a way to position his work as an organiser. This crystallised further when he started Kathmandu Photo Gallery in 2006, which led to even more curating work within the gallery and with other organisations. Kathmandu Photo Gallery alone has presented about 80 exhibitions to date.

As a curator and gallery owner, Manit says “I try to see how artists use photography, in their own way. When I started my own gallery, I intended to not just use it for commercial purposes, but also to have a space for photography.”

One of the ways in which Manit is doing this is through Project New Vision, which promotes the work of emerging photographers and photo artists.

Looking into the past to see the future

As he supports new photographic talent, Manit is also looking back into Thailand’s photographic history. He likens it to growing a healthy tree: “If you want a tree to grow tall, a tree needs to have deep roots. The taller the tree, the deeper its roots.”

If I want the photography to go forward, then I have to go backward, as well. I have to look at what has been done in the past, to understand the past so I can see the future.

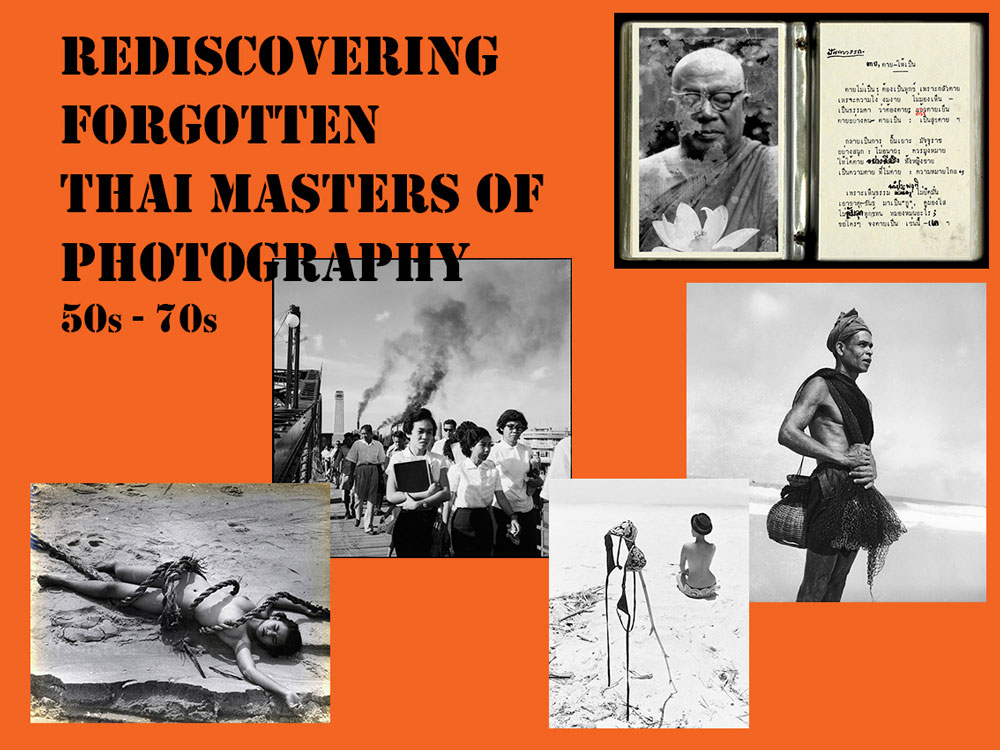

This was what ignited the Rediscovering Forgotten Thai Masters of Photography project, where Manit discovered the works of seven Thai photographers made between the 1950s and 1970s. The work was first shown in 2015 at Bangkok University Gallery, and has subsequently travelled to NUS Museum (Singapore) and ILHAM Gallery (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia).

“In the early day of the Thai photography, the photographs mainly depict the royal family and the aristocratic class. They were mainly made from the point of view of the high society. This is why the time frame for this project is 1932, because this is the start of the democratic revolution in Thailand. I want to see how photography affected the life of a Thai commoner, and through that see how people realised their own identities.

“When you are talking about democracy, people need to understand their own identity in order to exist. Democracy only works if you exist. If you don’t exist, there is no democracy. Photography is a way of validating our existence.”

“I want to show people that everybody has their own story. I encourage people to tell stories from their own archives. If you have a family item from say your grandfather, you might find something quite interesting, and that might lead you to something new.”

Manit continues his research into Thai photographic history. “Today I carry a camera less and less, and I go through archival images more and more, because I think we are able to work with the past, with existing images. How can we do it? How can they work? How can I make it come alive?” Delving into archival images has since resulted in new bodies of work such as Absolute Prisoners, 1902, and Lost.

You have to be honest with yourself

On advice Manit would give to artists looking to make socio-political work, he says, “I think first thing you have to be clear about is what you want to say and why you want to say it. This is important.

You have to be honest with yourself, and ask if this is a subject that you really want to deal with, or if you want to do it because it is trendy.

If you can answer those questions, then your next step is deciding what area you want to focus on, and why you want to do that. You have to fully understand your subject before you express yourself, because you shouldn’t comment on anything you don’t really know about. You have to understand the topic well, and then see how you’re going to talk about this topic, and how you develop that visual in your mind, how to manifest this idea, and what form it will take.

A good understanding of your topic is important because you need to answer to your audience. I am careful not to say anything about a topic I don’t know about. For example, I would not criticise Singapore politics, because I am not Singaporean. I don’t know Singapore political history well. It is dangerous to comment on something you don’t know about.”

Curation as generosity

On his generosity as a curator and practitioner:

I remember participating in an exhibition in Europe long ago, and I was invited to the show. At the exhibition, there were so many Chinese photo artists, and I was the only one from Thailand, from Southeast Asia. Being the only one was quite lonely, so how can I have more friends from Southeast Asia at such events with me?

I realised then, maybe I need to do something to promote Southeast Asian photography. That means we need to look at the ecosystem of photography. What do we need to grow this ecosystem?

Do we need a gallery? I will set up my own gallery. Do we need a photo festival to promote work? I helped to organise Photo Bangkok Festival in 2015 with my friend (Piyatat Hemmatat). I think the next step is to start a photo fair, to create a market for photography.

We have plenty of artists and photographers making work, but we also need collectors. We need a market for this work to close this loop, to make it a complete eco-system. We need to keep asking ourselves, what does our eco-system need?”

We have plenty of artists and photographers making work, but we also need collectors. We need a market for this work to close this loop, to make it a complete eco-system. We need to keep asking ourselves, what does our eco-system need?”

For recaps of other talks presented as part of Curatorial (Case) Studies:

- A Very Short History of Photography in Singapore by Charmaine Toh

- A History of Cinematic Exhibitions in Southeast Asia by May Adadol Ingawanij