On “The Black Dog Which Causes Cholera, and the Two Memorials of Plague”

Jim Lumbera and Joey Singh, a filmmaking duo who are the recipients of the Objectifs Documentary Award 2021 (Open Category), are presenting their exhibition The Black Dog Which Causes Cholera and the Two Memorials of Plague at Objectifs till end-April 2022. The show is a visual archive that rearticulates oral histories and local knowledge of the great cholera epidemic during the Philippine-American War.

The following recap presents highlights from their guided exhibition tour for the public and their conversation with the show’s curator Kamiliah Bahdar. Their conversations have been paraphrased and shortened for brevity. Much like the fluid and dreamlike quality of their work, their discussion too is deliberately meandering, peppered with anecdotes, and reflective in nature.

From L-R: Kamiliah Bahdar, Joey Singh and Jim Lumbera in conversation

Jim: Thank you to Kamiliah and Objectifs for helping us to develop this version. We didn’t know where it would go, but it’s been a really good collaboration. When Joey and I met, we were both questioning the images we had been making in the commercial industry.

We started to collaborate, and then believed again, in the image. We were chasing this “footprint” of a [metaphorical] dog… so there was always a feeling of mystery, of stories, of the people’s voices. We sought to collect and convey all these elements.

Kamiliah: Your photos show the beauty of the landscape and have a very dreamy quality to them. They are very much in stark contrast to colonial-era photographs which attempted to “fix” their subjects permanently, to make them hyper-legible.

But there’s this very traumatic history behind them. Working on this project required revisiting stressful, fear-inducing and even traumatic incidents such as war, the cholera epidemic and even the current Covid-19 pandemic.

Jim: We first acknowledged fear as a part of the process.

Joey: We got accustomed to the literal darkness we experienced in remote areas. The trees were comforting to us. Our experience paralleled what those who hid in the dark from the Americans felt. In the darkness, you feel more secure, because the landscape is still there. The silhouettes of trees were comforting to us.

Kamiliah: You also made an interesting choice to present the Taal volcano in a fragmented manner.

On the right-hand-side of this exhibition installation view, we see the depiction of the Taal volcano in a fragmented manner.

Joey: Jim and I examined the landscape to get a better view of how it is as an environment. We were at the volcano’s edge, photographing the main crater. Spatially, we could not just step back to capture a wider view. We would fall!

This experience felt like looking at Philippines history, where we also can’t just step back and look at it as one linear landscape. In our country, education about our history is always fragmented too. It’s very hard to piece it together and get a sense of what actually really happened.

The colonial era in the Philippines is very compact. Every day, something happened. It’s very exhausting. We were invaded by the Spanish… we were winning the war… and then the Americans came, and we were not independent anymore.

We had a split second of independence and then it was gone. Until now, that’s what Filipinos are talking about, even with the present situation in the country. For us, trying to stitch together different perspectives of this landscape gives us an idea of what’s outside the colonial framing of Philippine history. It’s very spatial, there’s so much more beyond…

Jim: We have been within that frame for a long time. So we either look from left to right, or right to left.

Joey: We would like to give a fresh perspective — that we are free to look in different ways. We encountered fragments of stories and couldn’t make out how they are connected to each other. But just putting them alongside each other, even if it doesn’t make sense, is how locals make sense of their past.

As a part of our process in coming up with the visual language we used, instead of photographing communities we started conversing with them and standing beside them and looking at what they are pointing at. So for most of our photographs that you see, we are standing beside them and then framing onto the landscape.

Joey and Jim give a guided tour of their exhibition.

Audience Member: Your show had many entry points from the dog, to cholera, to a volcano, and then the archives… It’s very fragmented. Could you talk more about framing and about nature and landscape as a way of archiving? You travelled and documented and archived but the documentary was already there. You were documenting a documentary.

And there’s a bit of chaos that you alluded to in your identity, history, where the Philippines is headed. Is it something to be afraid of, worried about? Or should we accept that that’s just the way it is and that having everything very clear and linear would get very boring very soon.

So you have a landscape that maybe tells you a story, or maybe not. When you come back tomorrow and stand at the same spot again, it tells you another story. And you meet all these people, and even though you’re all Filipinos, they’re probably strangers to you. So there’s a discomfort there, which I found in your show. It leaves me wondering what is actually going on.

Joey: Exactly. What you’re thinking is exactly what we are feeling, about mystery. This is an investigative project that tries to shed light on what really happened. Having an idea of what happened in our past would give us a better idea of where we are right now and where we are headed. That sense of confusion and irony at the same time is a feeling that still lingers in our present communities. Maybe that is why there is a very blurred line between what locals say, from inherited memories, about their history, and if there are any factual records like pictures to prove it.

That idea also leads us to question the dominant narrative — how real is it? Just because there is an old framed photograph, is it true to our history? Filipinos know more about our landscape than outsiders. Language also brings us closer to the truth.

It’s very sad to see that the younger generation believes that our history begins with the arrival of the Spanish and that progress begins with the arrival of Americans. There’s so much to know about our languages.

Audience Member: We have the same problem in Singapore.

Joey: It’s my first time in Singapore. Having such conversations with people here gives me both a sense of comfort and sadness that our problem with history is also felt in other countries as well.

Audience Member: You started with the story of the dog, and ended with the landscape. As an approach to crafting a frame. Singapore is not the Philippines. We used to have mountains but have never had volcanoes as far as we can remember.

For people trying to do a documentary on Singapore, the kind of framework and processes you created seem quite interesting. But you also have been able to start with a fragment of a story or an archive and then start to make sense of what you are looking at through your lens. What would you recommend for urban people like us in terms of conceptualisation?

Jim: The common denominator of all our exhibited images is silence. But it doesn’t mean we are using the silence to be silent.

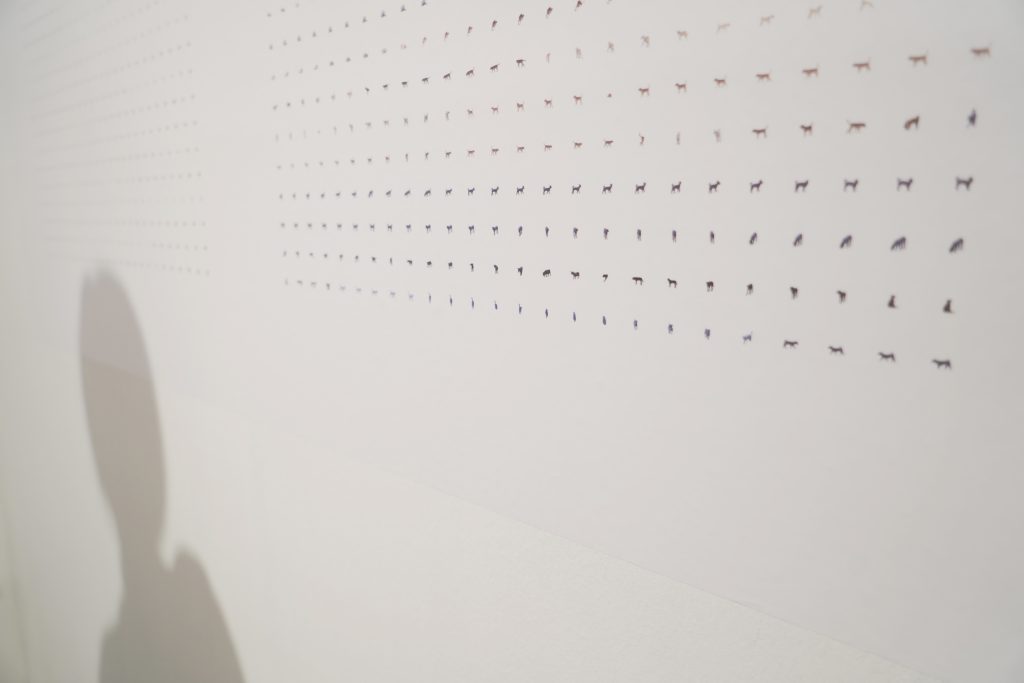

Joey: When we documented the dogs in the city… we were actually supposed to be documenting people who were still outside, or the conflict or tension in the streets, but there was none. So we made use of what was there. Looking at details beyond our expectations created opportunities to discover new mediums, new treatments…

A documentation of dogs in the city

Jim: We didn’t know what the exhibit would be. Each time we talked with Kamiliah, I was excited because it was a blank slate. It was scary too. We like to follow the image… we just believe there’s some image out there.

Joey: Try to hold onto what exists around you, and look for images of hope from there.

Jim: But you need a sense of community. If I just did this on my own, I’d feel crazy. It’s really helped that Joey and I created this with the community.

Audience Member: I find the black dog quite interesting as something you can also find in works from other cultures like the black dog in The Hound of the Baskervilles or in [the film] Stalker by Tarkovsky… I was interested in the Filipino tradition. What do you do with this dog that spreads cholera? Do you catch it, chase it away…?

Jim: When we arrived in Batangas, we asked about the black dog. One of the first leads we had was a conversation with my grandfather.

Joey: Jim’s grandfather is more than 90 years old and still very strong. He has a great memory. He grew up in the time when schools were raising both the Philippine and American flags. He remembers his father telling him about seeing the black dog. We have a saying that roughly translates to “do not greet the black dog, do not ‘recognise’ it, pretend it didn’t see you”.

Jim: If you ‘recognise’ it, you will get cholera.

Joey: It led us to wonder whether cholera is the actual disease, or something else that creeps into the bones of the Philippines.

Jim: Imagine, you’re looking for the black dog and your grandfather says not to ‘recognise’ it. I thought, So is this the end of my project?! [Laughter]

Joey: Should we stop our investigation?! [laughter] We stumbled upon an account that during the pre-colonial period the relationship of Filipinos with dogs was very intimate. They brought their dogs to the forest to hunt and farm. In Manila, there are remains of people buried alongside dogs. There is a belief that dogs guide you every day and so when we die, they will guide us too. So, we felt the black dog is a very strong symbol of the pact Filipinos had with dogs.

Joey: Spaniards in the Philippines believed that black dogs were bad omens. Our national hero José Rizal was assassinated in the short time between our defeating the Spanish and when the Americans came. A dog came up to his body at his execution in 1896.

Audience Member: I’m curious about your thoughts on the relationship between Catholicism and superstition.

Jim: Yesterday we were talking to Kamiliah about a book on passion and prayer. Passion is also a way of prayer for Spaniards. Even though we in the Philippines were converted into Catholicism we’ve always had our own traditions and rituals we’ve tried to stick to even as we perform the newer practice of Catholicism.

Joey: There is an old account that when the Spaniards came they were carrying an image of Santo Niño, a small child. Back then, we had a matriarchal system, so the image of a child had a certain symbolism. The embracing of Catholicism also roots from our oral tradition and our rituals of image-making.

Our belief is not fully anchored on Catholicism but it’s very close to our heart, our tradition. We had to embrace colonialism but also ensure our traditions survived. Even Filipinos made images of saints that are very foreign to us, faces that aren’t ours. We tried to hide these stories we cannot speak of in the Niños’ eyes.

Jim: If you see most of the saints, they look very sad and in despair.

Joey: It’s very surprising because when we were talking to the locals about the “black dog which causes cholera”, that kind of language is still there. At first you may think they are superstitious but when you ask them what it truly means, they see it more like wisdom instead of literally. There is a metaphoric image just so that we can pass it on. Words change, context changes over time. But the image, even if it’s the word for that image, can go on from one generation to another.

From L-R: Kamiliah Bahdar, documentary photographer Nhàn Tran from Vietnam, Joey Singh, Jim Lumbera, and Objectifs’ programme director Chelsea Chua

The Black Dog Which Causes Cholera and the Two Memorials of Plague by Jim Lumbera and Joey Singh is on view in Objectifs’ Chapel Gallery through 30 April. Admission is free.