On "Between the Silent Eyes", on young Hmong mothers

Nhàn Tran, a documentary photographer based in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and the recipient of the Objectifs Documentary Award 2021 (Emerging Category), presented her project in an exhibition at Objectifs in April 2022. Between the Silent Eyes focuses on young Hmong mothers in Hà Giang province, Vietnam, who marry and have children before the legal marriage age of 18.

The following recap summarises two talks Nhàn participated in: an online discussion, moderated by Chelsea Chua, Programme Director at Objectifs, with her mentor Hannah Reyes Morales, and an event in-person at Objectifs with photographer Juliana Tan. Their conversations have been paraphrased and shortened for brevity,

Between the Silent Eyes

Nhàn: I started researching Between the Silent Eyes in 2019. This long term project marks the turning point of pursuing my photographic practice in a more professional way, switching from a career in finance and banking.

I first visited some provinces in northern Vietnam, including Hà Giang. It was a totally new experience for me. I stepped into another culture in my diverse home country. The Hmong people welcomed me, took me around and invited me to a traditional wedding, where I met an 18-year-old girl who was already married, but preparing for her official wedding. She and her husband had evaded the law to move in together before they reached the legal age to get married.

When I returned to my city, I further researched the Hmong to better understand their way of living. I read about early marriage, which is a part of their historical migration and traditional nomadic life. I wanted to understand another way of life in a very different culture in my home country.

In early 2020, I photographed these young mothers for the first time when I got to know Máy via one of my friends who started a homestay business in the centre of Đồng Văn town. She was seeking short term work there before she would go off for her pregnancy. At 14, Máy illegally crossed the Chinese border and met a boy who became her husband. Now, she is a 19-year-old mother of two children.

I decided to prioritise my time to focus on Máy, because of our strong connection and relationship. She has a really strong character and knows what she wants, but she also knows she is disadvantaged as a minority person. Now, she is working hard in the city with hope for a better future for her children.

What I’m trying to tell with these portraits are not only her stories, but also the intimacy and the strong relationship we’ve built over time. My story depicts the young Hmong generation attempting to approach modernity within their tradition, who are trying to prevent this situation of early marriage from passing down to their children’s generations. It will take lots of time to see tangible change. But right now, I’m happy to see the younger generation realising the profound consequences of early marriage, and that they are actively taking action for themselves and knocking down doors. And I do believe that a better life will be waiting for them.

Nhàn’s foray into photography

Chelsea: How did your relationship with photography begin? What made you decide to pursue photography professionally?

Nhàn: Photography came to me very naturally in my 20s. When I was in university, I read many books on the human condition. One of my favourite writers is Khaled Hosseini, who is focused on the lives of people on the margins of Afghanistan society.

At that time, I usually tried to transform what I read into images, which was how I learned about photography. I started with street photography but soon felt dissatisfied with this genre as it didn’t allow me to build relationships with the people I photographed.

My work right now is just the very beginning of my own journey. Working with images is a happy task for me, and I can find happiness in photography no matter the circumstances.

Nhàn and Hannah on mentorship

Clockwise from top left: Chelsea Chua, Programme Director at Objectifs, Nhàn Tran, and Hannah Reyes Morales

Chelsea: Hannah, what drew you to Nhàn’s project?

Hannah: I was drawn to Nhàn’s project because she was asking the same questions I’m also drawn to in my photography. Questions about the human condition, how we as humans survive amidst different conditions, about the kind of perspectives we cast on the people that we are photographing.

She’s working on the very sensitive topic of teen moms. It’s not necessarily a topic that is new in the world of photojournalism. I have also done a story on teen motherhood [in the Philippines]. But I saw something different in her work. There were a lot more unanswered questions that I was really drawn to exploring together. We walked a lot together through the emotions we’d been feeling about the work, and this kind of topic.

Nhàn Tran introduces her exhibition to students from NTU ADM.

Nhàn: Experiencing feelings in isolation is a part of a photographer’s job. We have to convince ourselves every single day that we are on the right path. It’s not easy to become familiar with these feelings. Finding a community where you can feel a sense of belonging while engaging in your practice is very important. When a relationship grows with a mentor, we not only learn from each other about photography but also about how to protect our mental health, etc. There’s at least one person standing by you with whom you can share your thoughts and worries.

Hannah: Mentorship is about being in an ongoing conversation. It also takes a lot of chemistry; a personality match matters. My mentor Erika Larsen and I speak not just about our practice but also about being people in the world. It’s very enabling to have someone just take your work and your concerns very seriously. My experience inspired me to want to support others with their work too. I’m still finding my footing with teaching and mentorship.

Nhàn: With each conversation, the project was able to move forward. We printed out my photographs to assess the story’s direction. I wanted to convey through my images not only information but also my relationship with the people I photograph. But it was hard to convey intimacy visually, though I feel it in person when I interact with them.

Hannah advised that I’d need to take time to observe my feelings and try to translate them in my own photographic language. Back then, I felt in a rush. Patience has helped me gradually achieve that intimacy in my photography.

Storytelling techniques and tools

Chelsea: Nhàn, you were looking to do a lot with this project. Aside from taking photographs, you also did audio interviews, and you’re hoping to make a documentary film about the Hmong community. Hannah, many of your projects also use audio and moving images, in addition to still photography, to tell the story. As visual storytellers, how do you decide on the best way to tell the story?

Nhàn: Between the Silent Eyes is my first very first long-term project. I’m still discovering how to tell the story with various techniques and in more compelling ways. Right now, I’m deliberately choosing simple techniques — a traditional documentary approach with accompanying interviews. With the limited time I have when I’m far from home, I prioritise reading about local culture, experiencing local ways of living, finding between myself and local people, and building relationships with them.

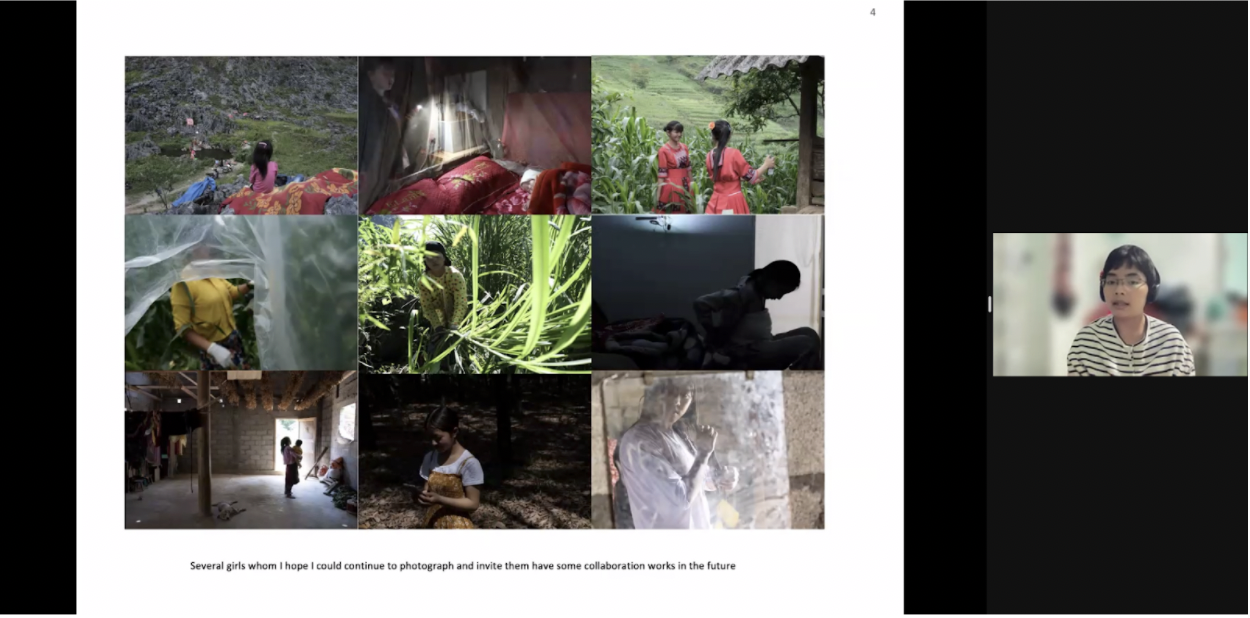

Nhàn Tran shares images from “Between the Silent Eyes”.

Hannah: I’ve been doing this for longer, and I’ve come to a point in my career where I feel the limitations of a still frame. Also just wanting to explore and remember what it was like when I first had a camera in my hand — what it was like to feel the awe and the wonder of seeing a moment and having that preserved through a camera. As the years roll on, things change. For me, adding new tools to my toolbox is a good way for me to continue having a sense of exploration when I’m out on the field.

It’s important to prioritise building relationships first but at the same time, having more tools sometimes helps deepen that connection. With other mediums such as audio, you’re allowing someone to just continue to talk. These things can be used as tools to hold space for other people. Each storyteller is different, but for me, the decision came when I started to really feel the gaps in what the images were saying. I’m a working photojournalist, so I get to work with a variety of people out in the field, such as writers and audio producers, and I get to see how they work to enable the subjects.

Creating safe spaces

Chelsea: You mentioned earlier that different tools can help you hold space differently for people, and how people react differently if they’re approached by a camera or by someone who’s looking to interview them for a film or through collaborative ways of expression. For both of you, since you deal with such sensitive and intimate stories with vulnerable communities, how do you create that safe space for your subjects or collaborators to share their stories with you?

Hannah: It’s important to be honest and clear from the start, that you are not making promises that this is going to change their lives. That’s one of the biggest things that I’ve had to reckon with since I became a photographer, because I’d thought it would change the world. A single image can’t do that, but it’s part of a bigger process, and contributes to more understanding. For photojournalism assignments, you don’t have the luxury of a long-term project, so you have to learn how to gain people’s trust and answer difficult questions quickly. You don’t have to strategise, it should come naturally.

I’m honest and straightforward about my intentions, whom I’m shooting for, who the audience is, what the risks are, and that there may not be any gains. Also afford your subjects the same dignity you would any other equal, and respect their space, even if it’s a humble one — remove your shoes, clear your own dishes, etc.

For stories in communities I’m not an insider in, I also make sure I have a trusted local with me as a guide. This doesn’t just apply when you’re outside your own home country. It may apply even with indigenous communities within my own country, for example.

Juliana: It’s important we don’t “parachute” into communities we want to document just for the sake of a story or project. In addition, the location you had to access was quite remote. How did you prepare to access it, both logistically and in terms of accessing your subjects?

Nhàn: Safety comes from trust we build over time. When I gain access, and make friends with someone, I really respect that relationship. I love and respect them and don’t want them to come to any harm. I always let them know what I’m doing and why I’ve appeared in their life. I print my images for them so they can see how they’ve been photographed and decide what they like and don’t like. They have the right to share with me their own perspectives on what I’m doing.

The development of Nhàn’s photographic practice and project

Juliana Tan and Nhàn Tran in conversation at Objectifs.

Juliana: How else do you plan to expand this project?

Nhàn: I see the exhibition at Objectifs as a first step in communicating this body of work to audiences. I’m interested in exploring the photobook as another format to present this work, to reduce the volume of information conveyed and increase the focus on visual language.

Audience Member: How has your photographic practice evolved while working on this long-term project?

Nhàn: At the beginning of my photography career, I took street photographs and captured quick moments around me. In 2019, I started this project and since then, my photographic approach has changed. Because I care about the people I meet, and I love taking time to build that relationship and earn that trust.

Over the past two years, my photographic approach has changed because what I am trying to do right now is spending time with people I meet, collecting materials from the outside world, and transforming it in a more personal way.

To be honest, I’m still finding my own language of photography and discovering what kind of photography will work for me. But photography is one of my happiest tasks, because it gives me time to understand people, to have this silent space and feel the power of that silence. What I am trying to bring out is the meeting point between myself and the people whom I meet.

Recap by Wenxin Gao

Between the Silent Eyes by Nhàn Tran is on view in Objectifs’ Lower Gallery through 17 April. Admission is free.

Objectifs is now accepting applications for the Objectifs Documentary Award 2022. Apply here by 24 April!