A conversation on recent works by Shwe Wutt Hmon with Guo-Liang Tan and Alecia Neo

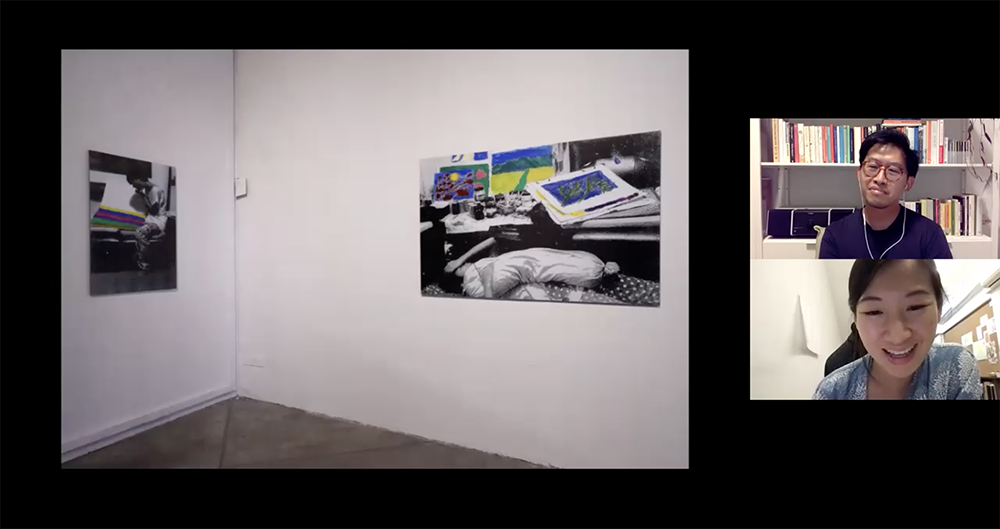

As part of Noise and Cloud and Us, artist-curator Guo-Liang Tan and artist Alecia Neo spoke about ideas and themes in Shwe Wutt Hmon’s latest work. Shwe is the recipient of the Objectifs Documentary Award 2020 (Open Category), and her first solo exhibition, Noise and Cloud and Us, was presented at the Chapel Gallery and curated by Guo-Liang. This recap of their discussion has been paraphrased and shortened for brevity.

Guo-Liang: Shwe and I have been working on this exhibition since last year, with many of our discussions taking place online. While she is unable to join us for today’s event due to the current situation in Myanmar and her personal circumstances, we hope that we are able to expand the dialogue around her work.

Alecia, you came to mind as an interlocutor for this discussion because of how you started off as a photographer, and how many of your projects now feature strong collaborations with other people around issues of care and caregiving. There is a strong resonance there with Shwe’s work for Noise and Cloud and Us.

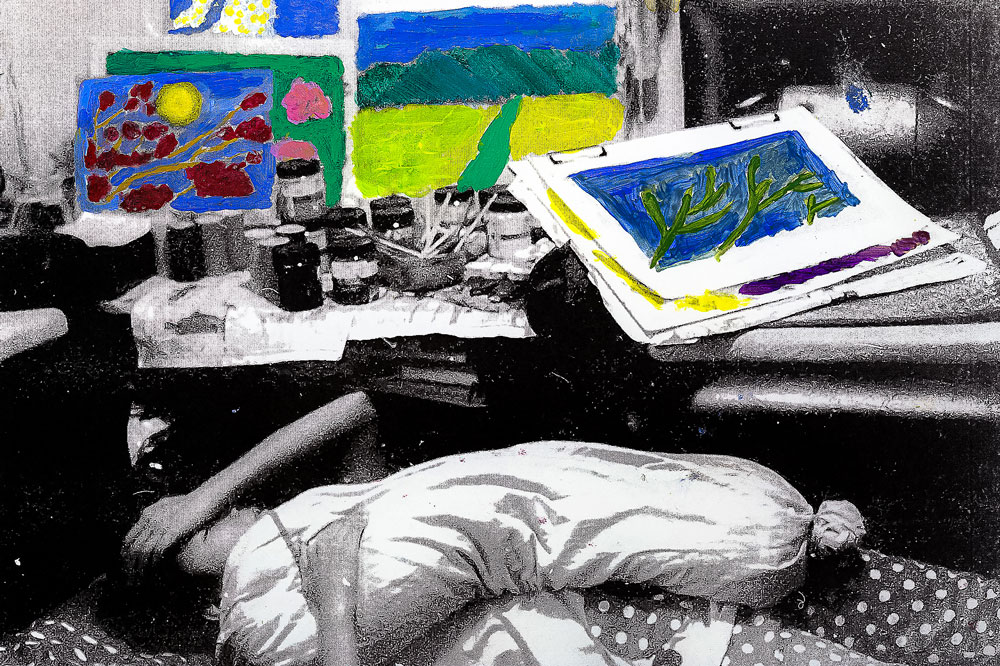

Alecia: I was thankful to learn about Shwe’s work, and my role here is very much one of a viewer, to reflect on the images and the process of making them. I was very moved by the exchanges between Shwe and Kyi Kyi Thar (Shwe’s sister), during the lockdown when this work was being created. I was reflecting on what Shwe shared in her video introduction, where she talks about how that period was extremely difficult for her, which is why she chose to make her images in black and white. And I thought that it was extremely courageous of her sister to insert colour into her images through painting, making these aesthetic choices about where she should intervene within the image.

I understand that Kyi Kyi Thar is also very much an artist in her own right, and that common artistic sensibility was what laid the foundation for their collaboration. From your discussions with Shwe, what were the challenges in trying to hold space for each other?

Guo-Liang: From the start of our working together, Shwe was very clear that she wanted to work with her sister on this project. Shwe started by getting her sister’s permission to photograph her, and then inviting Kyi Kyi Thar to paint on the photographs. Shwe would then scan the photograph that her sister had painted on, and print that as an image. As the project went on, Shwe thought about how their collaboration could be extended further, and this came about when her sister expressed an interest in photography. Shwe lent a camera to her sister that was loaded with colour film, just to see how Kyi Kyi Thar looked at the world. We decided to exhibit the results in the middle of the exhibition as a slideshow.

I think that the amazing thing about this project is the sensitivity that Shwe has, in not just involving someone else in the work, but to collaborate in a way that allows each of them to have an individual voice. It was very important to not just acknowledge Kyi Kyi Thar as someone who is struggling with mental illness, but to portray her as a creative individual. That perspective became more apparent as the project developed.

Alecia: I think it’s interesting to see how this series of work seemed to start off with Shwe’s own desire to make sense of the situation, and then became a space where both Shwe and Kyi Kyi Thar can heal and process their journey. I appreciated being able to see their journey in the work, moving from Shwe’s black and white photography, to mixed media, and then Kyi Kyi Thar’s coloured photographs. I thought that this was very revealing in the show, and it reminded me of some writing by a therapist, Esther Perel, whose therapeutic work often involves moving people from a position of stasis or stagnation into a place of movement, where they can imagine possibilities of growth and change their perceptions about a certain situation.

In many ways, the rawness of the images also give a sense of a lived aspect. In the process of making this work, was there a kind of breakthrough, or a change in perception or a new insight that occurred to the artist and collaborator, or for you as the show’s curator?

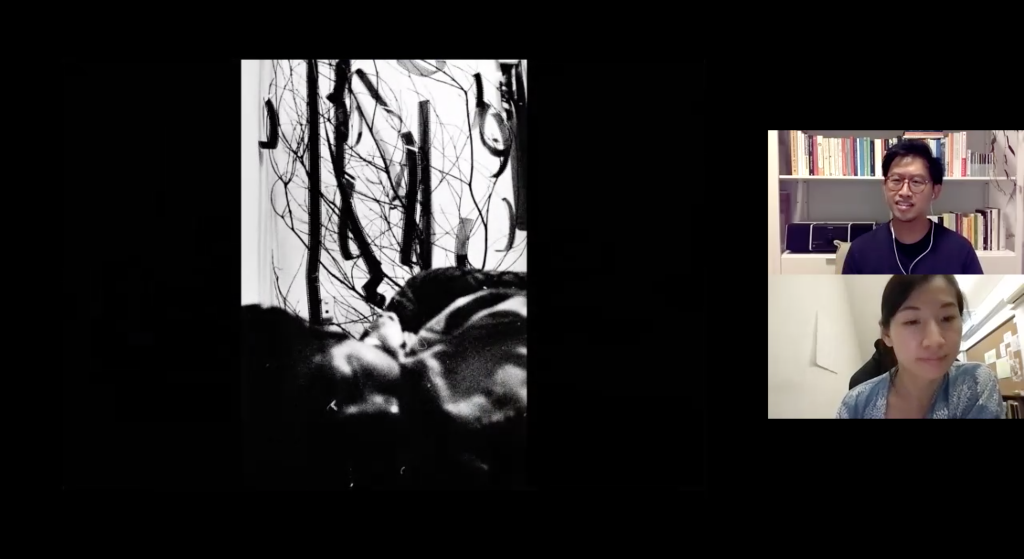

Guo-Liang: When Shwe proposed this exhibition, it was mainly images of her sister’s paintings on Shwe’s photographs. We really liked the images, and they were very affecting. But when she started to include other photographs, not just of her sister, but of daily life, I noticed that these images had a lived quality in their rawness, as you had mentioned. The black and white photographs were very grainy, and had a lot of visual noise, which was very interesting. Shwe shared that she used tap water to develop the images, which results in the appearance of these particles because of the quality of the water in Myanmar.

This idea of visual noise became very interesting for me, because it added a kind of atmosphere to the images, and an embodied materiality to the surface. If you have seen the exhibition, there is an unlit area at the back of the gallery where two speakers are playing a three-hour long recording. The recording is from the night Kyi Kyi Thar attempted suicide, where she heard voices telling her to take these pills. Her sister fortunately recovered from this episode, but she passed this recording to Shwe as evidence. Most of the time, what one actually hears is static noise, with occasional sounds of people moving around, dogs barking.

I think that was when the show clicked, and she decided on the title of the exhibition. The show became not so much about the pandemic, or her sister’s mental illness, but something more abstract. It was a really great moment, to realise that the work could go in another direction.

Alecia: Yes, many photographers struggle to keep a very smooth, clean surface for their images, and Shwe seems to have thrown that out of the window, and used the noise created by the particles in the water as an entry point into a mind space and a world that we might never be able to make sense of. I was particularly moved by some of the scenes she captured, which really captured a state of depression, a state of immobility that I think is actually what a lot of people who live with mental illness struggle with.

I think that it’s crucial that artists working with these issues deal with them sensitively, and I think that this show has done that. What are Shwe’s plans for the work, and her collaboration with her sister?

Guo-Liang: When we last spoke, Shwe definitely feels that the project has not ended for her. She’s keen to produce a book from this body of work.

Alecia, in your own journey as an artist, at what point did you feel like you needed to extend your photographic practice into something more collaborative?

Alecia: There were several projects that motivated me to do so. One of my first self-initiated projects was Villa Alecia, which was a site-specific work that comprised soundscapes and photo work installations. What changed my perspective on how I wanted to continue making work was when the show finally met the public. How people interacted with the space and the conversations that came out of it became more important than the work that we had made within the space. I have also been thinking about how the kind of work that I am doing, where I am working with other people, is often an act of listening.

Guo-Liang: I was looking at your recent projects, The Care Index and Between Earth and Sky, and I thought that those were interesting to think about in relation to Shwe’s exhibition because of the topic of caregiving. In Shwe’s case, her access point was well established because they are sisters. In your case, how do you decide on your collaborators and how do you negotiate the relationship with them?

Alecia: Between Earth and Sky was a year-long project commissioned by the Lien Foundation through Objectifs in 2018. It came at the moment when I had been participating in a peer to peer support group for caregivers, so it was the perfect opportunity for me to think about the process of healing, and understanding the different positions in caregiving. The project was also supported by an NGO called Caregivers Alliance, and it was through this organisation that I was able to invite caregivers to be part of the work. I learnt a lot about the stress of caregiving, how much of it is often physical, and the project centred on the body, how to express oneself through the body and potentially activate energy or hope for themselves or the situation. The work with body movement was done in collaboration with Sharda Harrison, who is a movement artist and theatre actor.

Guo-Liang: Yes, I see in yours and Shwe’s works, how body movement, painting and photography are a medium through which one is processing these difficult emotions, and thinking about the person who is giving care as well as the person receiving care.

Audience: Is this exhibition about understanding the person with mental illness better, or is it about them as a subject?

Guo-Liang: Kyi Kyi Thar’s struggle with mental illness was the starting point for Noise and Cloud and Us. But while there are parts of the exhibition that address this, the show on the whole has evolved beyond those concerns. The surprising thing about the exhibition is that even though the images are mostly in black and white, the show does not feel gloomy. It doesn’t feel like an exhibition about how difficult it is to cope with mental illness. I think what emerged through the work and the curation of the exhibition, is that this is actually about how two people see each other. You can of course see this in the context of caregiving, but I think that it can also be read as an expression of the close relationship between the two sisters. These things are not necessarily expressed in an exhibition blurb, but perhaps come through when one experiences the work physically in the space.

Alecia, do you have similar issues when you work with say caregivers, whether people just understand the work as saying something about caregiving, or whether you strive for a deeper understanding beyond that?

Alecia: It’s a fundamental struggle for me, and I’m trying to be more articulate about it. There is a tendency when making work in a particular space, where there are words like care, healing, mental illness or well-being, to contain it or see it in a certain way, to focus on the impact or the agenda, which the art-making doesn’t necessarily focus on. I’m also on a journey of trying to speak to audiences better, especially with a work that tries to reach very different people. I don’t think I’ve found the sweet spot yet.

Audience: How does Shwe’s work extend to a Singaporean context?

Alecia: The work strikes me as being very universal. A lot of people would probably know someone who is managing mental illness, or have experience caring for someone like that, and so I think that thematically it would relate to a local context.

I think the point that Guo-Liang made earlier was very important. I think the work offers a space of seeing, to encourage people to think about re-encountering a person who bears a certain stigma. The process strikes me as a dialogue, to think about what it really means to listen to someone, and what are the things you might discover in the process. It can apply to strangers, and different forms of stigma too.

____

:: To learn more about the show, read an interview with the artist by the curator here.

:: For a video documentation of the show, watch this video.