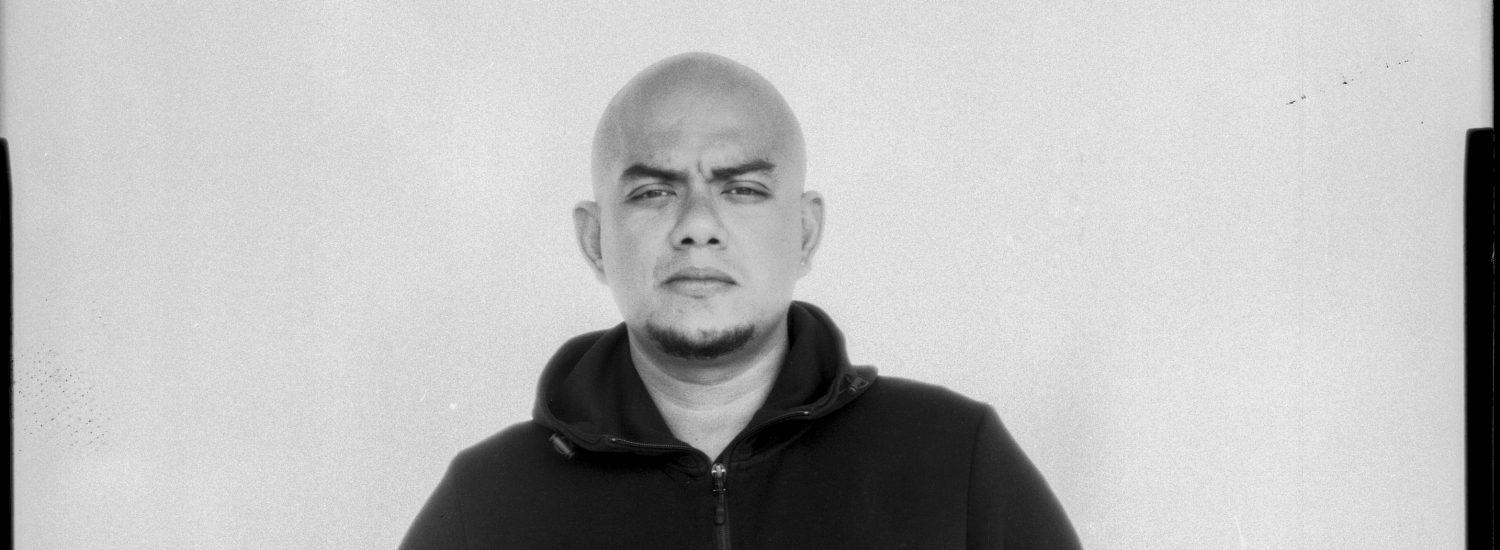

HEAR FROM THE JURY: VEEJAY VILLAFRANCA

Veejay Villafranca was born in Manila. He started out in journalism as a staff photographer for the national news magazine Philippines Graphic, covering socio-political events in the Philippines. After becoming a freelancer in 2006, he worked with several international news wire agencies before pursuing personal projects that later paved the way to his career as a full-time documentary photographer. In 2008, he was awarded the Ian Parry Scholarship and a residency at Visa Pour l’Image for his project on the lives of former gang members in Manila and in 2013 attended the prestigious Joop Swart Masterclass program of the World Press Photo Foundation. His works can be viewed at www.veejayvillafranca.com.

Veejay is based in Manila and works around the Asian region contributing to different news outlets while pursuing his personal work in the Philippines. He is a regular mentor for the Angkor Photo Workshops. Here, Veejay speaks about the importance of seeking guidance as a photographer, and how he has seen documentary photography change in Southeast Asia.

What role did mentorship play in your own development as a visual journalist?

Having a mentor is more of a luxury rather than a path, especially today where mentorship has been monetized and made into a revenue stream by some established photographers. I think this is a good diversification of our practice but also difficult for those who have no financial means.

I had several (unofficial) mentors so to speak – in the practice of journalism where I was tasked to churn facts and news into short articles no matter how horrible my grammar was, in photography where I was shown not the basics of the craft but the ways of seeing and visualization. I’m also fortunate to have guidance from established photographers and visual artists who emphasized the importance of critical thought and integrity in one’s work. Given all this, I believe that a photographer or visual journalist should actively seek and assert guidance and critical discussions for their work and also for their practice. This helps us have a wider view of our craft and of how our work can affect our audiences. It also helps us be adept with the current issues within our community and to adapt accordingly to the changes that are needed.

I believe that a photographer or visual journalist should actively seek and assert guidance and critical discussions for their work and also for their practice. This helps us have a wider view of our craft and of how our work can affect our audiences. It also helps us be adept with the current issues within our community and to adapt accordingly to the changes that are needed.

Has the idea of documentary changed for you over the years? What kind of developments in the Southeast Asian documentary scene have you observed?

There have definitely been much-needed changes in the practice of documentary in Southeast Asia in the areas of representation, ethics, and also professional practice. I grew up with the vision from the photographers coming from the west and how they visualized the world that they have seen back then. There’s nothing wrong with this, and this shows the dedication of those who came before us and gave us the inspiration and paved the way for us today.

But in recent years, documentary photographers have started to have a strong voice with regards to their own body of work. Photographers have been trying to reclaim narratives and representations of contemporary issues in their respective countries and I think that this is an amazing and important step towards diversity. The act of critiquing power structures with the use of images is continuous and growing even stronger in my opinion.

From ‘Barrio Sagrado’, © Veejay Villafranca

The Objectifs Documentary Award is now open for applications. The deadline for applications is 11 May 2020.

Read our interview with curator Guo-Liang Tan, here.